The

Ranums'

The

Ranums'

Panat Times

Volume 1, redone Dec. 2014

St. Cecilia and Conversions:

Marc-Antoine Charpentier's oratorios in honor of St. Cecilia,

as

expressions of the Guises' mission to convert Protestants, 1676-1686

For Shirley Thompson

Shirley Thompson's paper entitled "Charpentier and the Cecilian Tradition: A Comparative Study," presented at the international Colloque held at Royaumont in May 2013 (Les histoires sacrées de Marc-Antoine Charpentier: une histoire de genre), set me "musing" about the information I might be able to piece together about the four Caecilia's and the little Prologue added in 1686. Her thoughtful paper sent me delving into my file folders and our personal library, and downloading online versions of seventeenth-century books I had read decades ago, but with totally different goals in mind. What follows is the result of my quest: it must not be considered definitive, but I hope it will be of help to other scholars.

In 1675, twenty-six-year-old Isabelle d'Orléans turned to devotion

for solace. In 1672 she had lost her husband, Louis-Joseph de Lorraine,

Duke of Guise, to smallpox; now she was mourning the death of her only

child. As the king's first cousin, and as duchess of Alençon, she could

have decided to spend substantial sums on frivolous pleasures. She chose

devotions and charity instead.

By the fall of that year, 1675,

Marc-Antoine Charpentier created the first portrait in a musical gallery

of "histoires sacrées" (oratorios) that portrayed heroines and saints.

The first of these musical portraits is devoted to Judith, one of the heroines in Father Le Moyne's La Gallerie des femmes fortes. (1) This Jesuit father paints Judith (2) thusly: "A la mort de son Mary, [Judith]... vainquit la Douleur par sa resi[g]nation; et montra qu'avec le sang des Patriarches ses predecesseurs, elle avoit herité leur Foy et leur Constance." By prayer and fasting, Judith first conquered the "most dangerous ennemies of young widows": idleness, pleasures, and "lurking affections" (arrières-affections). Only then did she venture to conquer Holofernes.

A young widow. A widow who descended from the "patriarchs" of her nation. A widow known for her piety. Isabelle d'Orléans belonged to all three categories. If by chance she read Le Moyne's Gallerie, the parallel with Judith can scarcely have escaped her.

The "Moral Reflection" that follows Le Moyne's tale of Judith was

particularly pertinent to Mme de Guise's situation. When the arms of

Strong Men have grown weary, Le Moyne observes, and when wise heads have

felt exhausted, God has caused women to act, "il a suscité des Femmes."

Women do not encounter a Holofernes every day, he admits; but "every

day they must combat luxury, vanity, pleasures, all the agreeable

passions and the disagreeable ones." Let women therefore learn to

"reform their widowhood, and put themselves under God's yoke." Above

all, let them remain faithful to their dead husbands: "Qu'elles en

apprennent enfin, à garder la foy de la Memoire de leurs Marys decedez;

à ne faire jamais divorce avec leurs noms; et à mettre sous leurs

cendres tout le feu qui leur peut estre demeuré de reste." (In the

months that followed her husband's death, Isabelle had hoped that Louis

XIV would arrange a prestigious second marriage for her. That hope was

quickly dashed. For the rest of her life she dressed as a widow; and,

honoring her dead husband and son, she continued to go by the name of

"Madame de Guise," despite having renounced all claims to Guise

possessions.)

Femmes fortes and saints, as models of conduct

Under these circumstances, should we be surprised to find, in cahiers

9-11 of Marc-Antoine Charpentier's autograph Mélanges, a long piece

about Judith (H.391)? This work must have been written for a hired

musical ensemble, because the group I call the "Great Guise Music" did

not take shape until the mid-1684. From the chronological arrangement of Charpentier's compositions, and from the handwriting, we know that

Judith sive Bethulia liberata dates from late September 1675.

Two

years later, should we be surprised to find, in cahiers 17-18, a "story"

about Esther (H.396, Historia Esther), written for the same ensemble of

hired musicians? (3) No article in Le Moyne's

Gallerie was devoted to Esther, but he believed that she merited a place

there: "Cet exemple [Judith] n'est pas l'unique de son espece. ...

Esther sauva [son peuple] des mains d'Aman et du massacre general qui

luy estoit preparé par toute la Perse." (4)

Two femmes fortes to emulate. Two "stories" about them, performed by what appears to be the same group of hired musicians, but separated by two calendar years, almost day for day. By commissioning these histoires sacrées, Isabelle d'Orléans was proclaiming publicly her intention to devote her life to prayer and pious deeds, and to remain faithful to the memory of her late husband, the last adult male of the House of Guise. (The current state of research does not permit identification of the place where these musical statements were made, but I have proposed that the venue was the Theatine church of Sainte-Anne-la-Royale. (5))

In November 1676, Charpentier had written a third work about a heroic woman. This time the heroine was a saint and a martyr. Charpentier called it a "canticum" (a "song"), rather than a historia: In honorem Caeciliae, Valeriani et Tiburtij Canticum (H.394, in cahier 13). Strictly speaking, the work was "in honor of" three martyrs, not just one: St. Cecilia, her husband St. Valerian, and her brother-in-law St. Tiburtius. This "song" was written for the small group of performers (d, hd, b, two treble instruments and continuo) that I call the "Guise Core Trio." (6) Pieces for this group had appeared in Charpentier's notebooks for the first time earlier that very year.

Slightly more than a year later, November 1677, Charpentier would write an expanded version of this work. The point of departure was the libretto he had used for the canticum; but he modified the title to read Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus (H. 397). In marked contrast to the "song" for the three martyrs, this work required a large (and presumably hired) group of musicians that differed only slightly from the ensembles who had performed Judith and Esther.

Then, in late 1679, came a musical portrait of St. Charles Borromeo during the plague of Milan: Pestis Mediolanensis (H.309). This piece almost certainly was intended for an event sponsored by one of the Paris branches of the Confrérie de la Charité, of which Mme de Guise was an active member, indeed, a "Superior." Here too, the ensemble probably consisted of hired musicians. The relative brevity of this work surprises: I can propose no reason.

Schematically, here is a table that shows the chronology of the compositions about virtuous women and courageous saints, the ensembles who performed the works, and the number of measures in the piece:

Date in chronological order, type of ensemble, number of measures.

late Sept. 1675 Judith sive Bethulia liberata (H.391) 2hd, hc, 2t, 2b; chorus, 2 flutes, 2 violins, BC (organ) 1012

Nov. 1676 In honorem Caeciliae, Valeriani et Tiburtij. canticum (H.394) hd, d, b, 2 treble instr. and BC 209

late Sept. 1677 Historia Esther (H.396) 2hd, hc, 2t, 2b; dbl chorus, flute, 2 violins, BC (organ) 643

Nov. 1677 Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.397) 5hd, 2hc, 2t, b, dbl chorus, string orch., BC (organ) 908

Nov. 1679 Pestis Mediolanensis (H.398) 2hd, 1hc, 2t, 2b, dbl chorus, 2 flutes, dbl string orch., BC (organ) 340 plus later prelude

Then, after a hiatus of 7 years ...

Nov. 1684 Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.413) Great Guise Music 677

Nov. 1685 Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.415) Great Guise Music 381

Nov. 1686 prologue for H.415 1 dessus and 2 treble instruments (Guise?)

A closer look at this chronology and at the musical ensembles, suggests that from 1675 through 1679, Mme de Guise was commissioning an entire cycle of oratorios about heroines and saints. The events portrayed in these works either mirror her own life or evoke a charitable or devotional activity in which she participated. The cycle consisted of Judith, late September 1675; Esther, the final days of September 1677; Caecilia Virgo et Martyr, November 1677, and Pestis Mediolanensis (St. Charles Borromeo) in late 1679.

Note that H.379 was recopied (and probably reworked) circa 1683-1685, then put back into its original time slot in Charpentier's chronological filing system. In her paper for Royaumont, Shirley Thompson discusses the importance of this recopying date and refers readers to Catherine Cessac's "Chronologie raisonnée des manuscrits autographes de Charpentier," Bulletin Charpentier, 3 (2010-2013), Tableau récapitulatif, p. III, available from http://philidor.cmbv.fr/bulletin_charpentier.

I have shown H.394 in bold type, because it simply does not match the other portraits in the gallery, either in length or in its rather atypical combination of voices. (I do not believe that the works written in the 1680s for the Great Guise Music belong to this cycle; rather, I see them as reflecting the devotions of Marie de Lorraine, the last duchess of Guise, known to her contemporaries as "Mademoiselle de Guise.")

Saint Cecilia

Father Le Moyne's Gallerie did not extend to Christian martyrs, so Mme de Guise cannot have come upon the story of St. Cecilia while thumbing through the Jesuit's book, seeking a heroine to honor. Then too, although she had been schooled in Latin as a girl, to prepare for being abbess of Remiremont, it would be hazardous to imagine her thumbing through the Latin text of Jacobus de Voragine's late fifteenth-century collection of hagiographies known as the Legenda aurea, the "Golden Legend." (7)

Yes, the Legenda aurea turns out to be the source upon which all the libretti honoring St. Cecilia are based.

And, according to an unimpeachable source, the author of those libretti is Mlle de Guise's "chapel master," Philippe Goibaut des Bois, also known as "Monsieur Du Bois de l'Hôtel de Guise." (8)

That is to say, the resident in Paris for the Grand Duke of Tuscany credited Du Bois with writing the libretto for H.415, that is, the Caecilia of November 1685. Since only minor changes distinguish the previous three libretti from this final version, it presumably is safe to assume that Du Bois wrote all the texts for all four Caecilia's.

When creating these texts, Du Bois did not stitch together bits and pieces of Voragine's Latin text, in a patchwork-like paraphrase. He did not, however, consider an exact quotation to be beneath him. Indeed, he borrowed with exactitude two antiphons for Cecilia's feast day and retained them in all versions of the libretto. He did however interpolate a short phrase into the first antiphon, and he inverted the order of the word groups in the second. The first borrowing serves as an opening line in each version of the libretto: Est secretum, Valeriane, quo tibi volo dicere. Angelum Dei habeo amatorem qui nimio zelo custodit corpus meum; and the next borrowing comes soon after: Valerianus in cubiculo Caeciliam cum angelo orantem invenit. (9)

Aside from these two quotations from the liturgy, the Caecilia libretti almost certainly are Du Bois' own version of the saint's life, as he found it recounted in the Legenda.

As an example of how Du Bois recounts the Legenda in his own words, take his Fac ut aqua baptismalis occulorum mentis tuae calignem dissipet. Angelum Dei videbis zelatorem et custodem virginitatis meae. ("Let but th'all-curing water of baptism dispel the darkness from thy heart. Then shalt thou see God's angel, zealous guardian of my virginity.") It is based on the following words from the Legenda: Cui Caecilia dixit: si in Deum verum credideris et te baptizari promiseris, ipsum videre valebis ("Cecilia answered to him: 'If you will believe and baptize thee, you shalt well now see him").

On the other hand, Du Bois invented the passages about singing, choirs of angels, and instruments. The only music or musical instrument mentioned in the Legenda is the organ, which Cecilia heard at her wedding: ...Et cantantibus organis illa in corde soli domino decantibus... ("Hearing the organs making melody, she sang in her heart, only to God...").

In addition, the vocabulary chosen by Du Bois is markedly different from that of the Legenda. He was sufficiently sure of himself to paint word-pictures in his own words, carefully choosing his vocabulary so that the sound of the words would enhance the effect of the word-pictures he was painting — which were, of course, word-pictures that Marc-Antoine Charpentier would be transferring to music.

The story of Cecilia according to the Legenda aurea

What is the story of Cecilia, as preserved in the Legenda aurea? (The quotations in English come from the quaint version cited in note 7.)

According to the Legenda, Cecilia was born in the second century, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Her family was noble. Raised a Christian, she vowed to remain a virgin. When her family arranged a marriage with a young pagan named Valerian, she renewed this vow as she heard the organ playing. On her wedding night, in the bedchamber, Cecilia said to Valerian: "O, my best beloved and sweet husband, I have a counsel to tell thee. I have an angel that loves me, which ever keeps my body ... and if so be that you love me in holy love and cleanness, he shall love thee as he loves me and shall show thee his grace."

Valerian wanted proof that this was the "angel of God." In reply, Cecilia told him to go out along the Appian Way, to be baptized by Pope Urban, who would be awaiting him. There Valerian had a vision: an old man read from a book written in gold: "One God, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, above all, and in us all everywhere. Believe you this?" said he. Valerian cried out: "There is nothing truer under heaven." (This exclamation apparently sufficed to serve as Valerian's Profession of Faith.)

Having been baptized by Urban, Valerian returned to Cecilia and found her in her chamber, speaking with an angel, who was now visible to Valerian. (10) The angel gave each of them a crown of roses and lilies, saying: "I have brought them to you from Paradise, and they shall never fade, nor wither, nor lose their savour, nor they may not be seen but of them to whom chastity pleases."

Not long afterward, Valerian's brother, Tiburtius, entered the room and "felt the sweet odor of the roses and lilies, and marvelled from whence it came." (Because he had not been baptized, he could not actually see the flowery crowns, he could only smell them.) "If you wilt believe," Cecilia told Tiburtius, 'you shalt see the crowns of roses and lilies that we have." She and Valerian began to tell Tiburtius of "the incarnation of our Lord, and of his passion." Tiburtius was converted and baptized, and "from then forthon he had so much grace of God that every day he saw angels" — and presumably his personal flowery crown as well. The angel had informed the two converts that "Ye both shall come to [our Lord] by the palm of martyrdom,"; stalwartly, the two men nonetheless went about converting others.

Eventually Almachius, the provost of Rome who was putting many Christians to death, learned that Valerian and Tiburtius were distributing their possessions to the poor. When the two young Christians refused to offer sacrifice to a statue of Jupiter, Almachius ordered their beheading. This did not stop Cecilia from working to convert pagans and getting them to agree to being baptized, even though it would lead to martyrdom. "In the hour of their passion [witnesses saw] angels clear shining and their souls ascend into heaven, which the angels bare up." Almachius soon summoned Cecilia, who immediately began preaching to him: "Your power is little to dread, for it is like a bladder full of wind, which with the pricking of a needle is anon gone away and come to naught. ... Now shall I prove thee a liar against the very truth." Enraged, Almachius ordered her to sacrifice to the gods. She replied: "Them that you sayest be gods we see them stones." In vain did Almachius try to kill Cecilia by placing her in a burning bath: "to her [it] seemed a place cold." Next he ordered her beheaded in that same bath; but although the executioner injured her mortally, he could not remove her head. She lingered for three days, "and gave all that she had to poor people, and continually preached the faith all that while; and all them that she converted she sent ... for to be baptized." At the end of three days "she slept in our Lord" and her house was "hallowed into a church [Santa Caecilia in Trastevere, in Rome], in which unto this day is said the service unto our Lord."

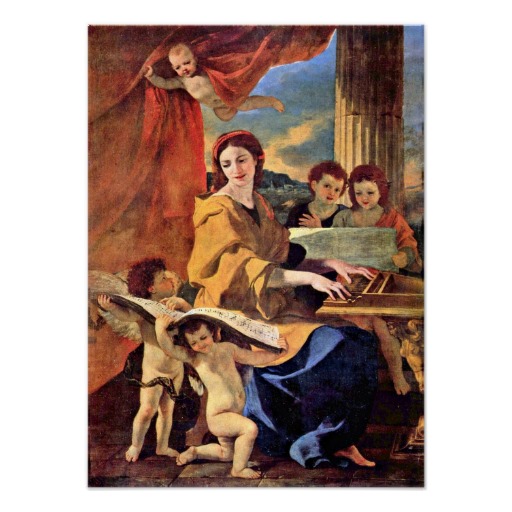

It will perhaps be helpful to compare, in translation, the content of a bit of Voragine's text (circa 1260) and snippets from Du Bois' libretto for H.397. (The translation of Voragine is a somewhat modernized version of Caxton's translation of 1483; the translation of Charpentier's libretto is the pseudo-archaic one done by John Underwood for Louis Devos's CD of H.397, which I am using here so that readers can locate that passage in Du Bois' Latin libretto.) This comparison will serve a dual purpose: not only does it show how heavily Du Bois relied on Voragine, it also helps clarify the role that baptism and accepting Jesus Christ played in rendering the angel visible. (11) (12) (To evoke the time of Voragine and Caxton, I show first a painting by Botticini, circa 1430: Cecilia stands between Valerian and Tiburtius: above them hovers an angel with a wreath of red and white flowers.

Voragine did not invent the iconography: the second image shows Cecilia, Valerian and Tiburtius crowned by the angel, from the "St. Cecilia Bible" (circa 1098).

Voragine versus Du Bois’ libretto

Voragine:

And Valerian, ...

said to her: "If you wish that I believe that you say to me, show to me

that angel that you speak of, and if I find veritable that he be the

angel of God, I shall do what you say ..."

V: "Caecilia dear, my

heart’s delight, my love, what faith thinkst thou that I can have in

these thy words if first I have not seen that guardian which thou

speakest of?"

Cecilia answered to him: "If you will believe and

baptize thee, you shalt well now see him."

C: "Let but th’all-curing

water of baptism dispell the darkness from thy heart. Then shalt thou

see God’s angel, zealous guardian of my virginity."

Then Valerian received baptism ... and returned home to Saint Cecilia, whom he found within her chamber speaking with an angel. And this angel had two crowns of roses and lilies which he held in his hands, of which he gave one to Cecilia, and that other to Valerian...

Chorus: "And once with holy water blest, Valerianus finds Caecilia closeted with the angel, praying. The angel then offers them both flowers, which give off the sweetest scents."

Tyburtius... entered into this chamber, and anon he felt the sweet odour of the roses and lilies, and marvelled from whence it came. Then Valerian said: "We have crowns which thine eyes may not see, and like as by my prayers you has felt the odour of them, so if you wilt believe you shall see the crowns of roses and lilies that we have."

Then Cecilia and Valerian began to preach to Tyburtius of the joy of heaven ... and of the pains of hell, and also they preached to him the incarnation of our Lord of his passion, and did so much that Tyburtius was converted and baptized. .. And from then forthon he had so much grace of God that every day he saw angels ...

Du Bois:

V: "Caecilia dear, my heart’s delight, my love, what faith thinkst thou that I can have in these thy words if first I have not seen that guardian which thou speakest of?"

C: "Let but th’all-curing water of baptism dispell the darkness from thy heart. Then shalt thou see God’s angel, zealous guardian of my virginity."

Chorus: "And once with holy water blest, Valerianus finds Caecilia closeted with the angel, praying. The angel then offers them both flowers, which give off the sweetest scents."

T: "Oh sweet, oh marvellous scent, unseasonable, who gave you these fair blooms?" C and V: "God’s angel ‘twas who gardeth us." T: "I stand amazed, how can I credit it?"

C and V: "Tiburtius, look in the skies, behold the earth, the streams, and see all the things they hold: thinkst thou that He who by his word and deed created all could not such wonders do?" T: "I recognize thee, O Christ." V and T: "And now as one, swear we our faith in Christ, we recognize thee, O Christ, we invoke thee O God..."

In other words, only if one makes a confession of faith in Jesus Christ will the angel become visible, Only the baptized can see the angel that bestows the flowery wreath on Christians. People who have not been baptized can merely smell the flowers of the wreath.

Some Roman representations of St. Cecilia

During the two or three years that Charpentier spent in Rome, he may have had occasion to admire some famous images of St. Cecilia. (13) It is, of course, possible that he was oblivious to what his eyes were seeing, and that his mind was focused instead on the sound-painting that his musical ear was "seeing."

In the 1660s, visitors to the church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere could admire two paintings by Guido Reni. One of them is this tondo by Guido Reni depicting Cecilia, Valerian and the angel. (14)

The other painting, not shown here, shows the executioner about to behead the saint.

In the same vein, we can hypothesize about whether Charpentier paid a visit to San Luigi dei Francesi, the French church of Rome. This does seem likely, because the Feast of Saint Louis was celebrated there every August, as were special events sponsored by the French ambassador. (15)

For the Polet chapel at San Luigi (dedicated to St. Cecilia), Domenichino had painted, circa 1610, a cycle of frescoes based on the Legenda aurea. His five tableaux form an interesting parallel with the word-pictures that Du Bois painted a half-century later. Indeed, Domenichino's frescoes, and Du Bois' libretto, provide examples of the images that the Legenda could suggest to two "artists" living in different countries and working in different "media." Monsieur Du Bois subdivided the story of Cecilia, as recounted in the Legenda, into what could be described as a cycle of seven verbal tableaux:

1) The angel

gives flowered wreaths to Cecilia and Valerian;

2)

Tiburtius is converted and sees the angel;

3) they

make a profession of faith;

4) called before

Almachius, Cecilia preaches to him, refuses to offer a sacrifice to

Jupiter;

5) her execution is ordered, but she does

not die immediately: she lingers for three days and distributes her

possessions to the poor;

6) she dies surrounded by

Christians;

7) she rises to heaven where she

receives a martyr's crown and palm.

For roughly a decade, Du Bois periodically revived his libretto, adding or subtracting tableaux, and modifying one or another of them, as appropriate for the circumstances.

(The number in parenthesis before the description of each fresco refers to my numbering, above, of Du Bois' seven verbal tableaux.)

Domenichino’s five tableaux

(1) Cecilia, Valerian and the angel, who holds two crowns — Behind Cecilia is what appears to be a little yellow organ, the only instrument mentioned in Voragine’s story.

(4) Caecilia before Almachius — She refuses to offer a sacrifice to the statue of Jupiter in the background.

(5) Cecilia distributes all her possessions to the poor — In the top right corner, the severely injured saint can be seen reclining. (Du Bois’ libretto merges the charity done by Valerian and Tiburtius prior to their martyrdom, and the charity that Caecilia did on her deathbed.)

(6) Cecilia dies — Pope Urban watches from the far right, and an angel hovers above, holding a martyr’s palm frond and golden crown.

(7) Cecilia’s apotheosis — Putti carry the sword with which she was beheaded, the martyr’s palm, and the crown of golden leaves. The larger angel to the right carries a tiny yellow organ.

The parallel is striking between Domenichino's imagery and the imagery that Du Bois wove into his libretto. (16) Yet Du Bois apparently never set foot outside France. If he was aware of the iconography in the chapel at San Luigi dei Francesi, his awareness almost certainly came from his collaborator, Charpentier.

Should the parallel that I am drawing here be restricted to the images suggested by the Legenda aurea and those in Du Bois' libretto? Should we instead parallel the three sides of a rhetorical triangle: Domenichino (1610), the Legenda (circa 1260), the Cecilia librettos (1676)? That is to say, the Legenda furnished a story that could be subdivided into at least seven tableaux, or even as many as ten. Any number of artists, poets and musicians could use those tableaux as a point of departure for their own creativity. Domenichino presented five of those scenes, and he did it according to the art of pictorial rhetoric. He did it so masterfully that François Nodot, a French visitor to Rome, praised the paintings at San Luigi dei Francesi thusly: "L'expression des choses est si parfaite, qu'elle imite la nature au dernier point." (17) (The words expression and imiter la nature had profound rhetorical resonances for late-seventeenth-century Frenchmen. (18)) Du Bois subdivided the Legenda into surprisingly similar scenes; then Charpentier enhanced Du Bois' verbal tableaux by choosing the appropriate musical colors and rhetorical devices. Indeed, when praising Charpentier's settings of Latin texts, the Journal de Trévoux likewise employed the vocabulary of rhetoric: expression, grands effets, tons. Some of these tones and these "grands effets" are described by Catherine Cessac:

Le trouble qu'éprouve le frère de Valerianus est rendu ... par l'utilisation, tout à fait exceptionnelle, du quart de ton noté x...; ... ce trio au style arioso suave comme le senteur des fleurs ...; ... jusqu'à la conversion de Tiburtius, celui-ci d'un part, les deux époux de l'autre, utilisent un matériau thématique différent; dans une deuxième partie, les trois personnages, unis dans la même adoration divine, se rejoignent en un chant identique ...; ... Caecilia va mourir. Modulation en mineur, sublimes harmonies, silences, mélodie qui brusquement s'interrompt au milieu d'une cadence .... (19)

I searched in vain for French paintings based on the verbal images suggested by the Legenda aurea. Of the images in Albert Pomme de Mirimonde's collection (available on Gallica.fr), the only pictures with an angel holding flowery wreaths were Guido Reni's tondo (!), plus a few Northern European paintings by Flemings or Germans (Woensaur, Hülsman), who, I suspect, spent some time in Italy. Nor, beyond a drawing of Domenichino's apotheosis of Cecila, did Mirimonde's collection include representations of the subjects depicted in the San Luigi frescoes.

Indeed, the gulf is broad between the iconography at San Luigi dei Francesi and the works of French painters who flourished during the first half of the seventeenth century. In France, St. Cecile seems generally to have been portrayed playing an instrument and accompanied by one or more cheerful angels.

Hoping to unearth parallels between Du Bois' text and French religious literature, I consulted the index to Henri Bremond's Histoire littéraire du sentiment religieux en France. In that study, which focuses exclusively on the seventeenth century, Cecilia is not there. Nor does there appear to have been much poetry written about St. Cecilia during the seventeenth century, akin to the English odes that were honoring the saint. Finally, I searched the online catalog of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, as well as WorldCat; I could find no seventeenth-century translation of the Legenda aurea into French, (20) to be used by pious laymen and laywomen whose Latin was shaky or nonexistent.

In short, the verbal iconography in Charpentier's several pieces honoring St. Cecilia differs markedly from the visual images of the saint that decorated Parisian salons and cabinets during the 1670s and 1680s. (21) In fact, it is difficult to imagine that the audiences listening to his pieces about Cecilia would have conjured up, in their mind's eye, a woman sitting at a keyboard, or playing a viol, in the presence of a cluster of admiring young angels. The "tones" of voice, the harmonies, the melodies in Charpentier's Cecilia cycle depict a very different Cecilia! The strong religious bent expressed in the libretto, colors the ambiance of each Caecilia. She is not a musician, she is a virgin missionary who willingly becomes a martyr. Sometimes tableaux 1, 2 and 3 are the libretto's sole focus. Sometimes a second part is added, to recount the events in tableaux 4-7.

At first glance the libretto appears to change little from one version to the next. A closer reading of the evidence reveals just how significant these seemingly minor changes are. For example, all four versions focus at length on conversion and baptism, that is, on tableaux 1-3. But some of the versions (H.394, H.415) recount only those first three tableaux (the angel with the flowery crowns, and Valerian's and Tiburtius' conversions and baptisms), while other versions, (H.397, H.413) add a second part that depicts the events in tableaux 4-7 (Cecilia's lecturing of Almachius, her subsequent martyrdom, her giving away her personal wealth, and her apotheosis).

These variations in length and wording reflect distinct moments in the religious lives of the two Guise women, and the political pressures to which they and their entourage were responding. I have succeeded in assembling quite a bit of information about the political and devotional contexts in which the first and the last Caecilia were composed. In both instances, the contexts involve the conversion of Protestants, during the decade leading up to the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes that was decided in August 1685 and signed on October 22 of the same year. (22)

The

Four Caecilia's of Du Bois and Charpentier

Cecilia no. 1: In honorem Caeciliae, Valeriani et Tiburtij canticum (H.394): an abjuration at the Jesuit Novitate, November 1676

During the autumn of 1676, Mme de Guise was sheltering a Huguenot woman in her vast apartment at the Luxembourg Palace, more commonly known as the "Palais d'Orléans." Her guest was the demoiselle de la Tour Gouvernet, sister or daughter of the count de Paulin. She came from Pau in Béarn, the Protestant region in the Pyrenees that was the birthplace of King Henri IV. (I have been unable to determine her first name and her exact relationship to the Count.)

For the week of November 21 (no precise date was provided, but the event had taken place "ces jours passés") the Gazette de France, the official journal that spoke for the Monarchy, informed its readership that, at the Jesuit Novitiate, Mlle Gouvernet had abjured (23) her Huguenot faith and had converted to Catholicism "entre les mains du Père de la Barre, en présence de Mme de Guise, qui luy avoit donné retraite, par ordre du Roy, dans son Palais d'Orléans; où elle a esté instruite durant plusieurs jours." (24)

The Gazette emphasizes that Mme de Guise was doing this at the request of her royal first cousin, Louis XIV. Louis continued to believe that a gentle approach to the Huguenot problem was preferable to a harsh one: "I believed," he would later tell his son, "that the best means of reducing the Huguenots little by little ... was not to press them with any new rigor, to recognize what had been accorded to them by my predecessors, but to allow them nothing beyond that and to reduce [their rights] by administration, to the smallest extent that justice and bounty would permit." (25)

Mme de Guise was animated by a sense of mission equal to that of her royal cousin. Indeed, she seems to have been determined to convert the several thousand Huguenots who lived in her duchy. She wanted to accomplish this by using what was described as the "méthode pacifique" — that is, reason and gentle persuasion rather than physical force.

To this end, just eight months earlier (March 12, 1676) she had created a house for "new Catholics" in her duchy of Alençon, to serve as a "refuge for abjuring heresy." A girl who decided to convert would first make a civil abjuration before the lieutenant général, who would draw up a statement about her commitment and would countersign it. This was a purely administrative declaration to the effect that she had renounced the "So-called Reformed Church" (Religion prétendue réformée, or "R.P.R.") and intended to join the Catholic Church. The convert would then withdraw to the House and, after two or three months there, would make her religious abjuration. (26) (Mlle Gouvernet's "retreat" at the Palais d'Orléans presumably followed on the heels of a civil abjuration.) On the day of the abjuration, she was presented by a woman for whose good faith the Catholic community could vouch. (Mme de Guise played this role at the Novitate that day.)

What was the abjuration ceremony like?

Jean-Jacques Rousseau recalled his own abjuration (27); he claimed that he returned to the bosom of the Church via the "same ceremony observed for Henri IV." He recounted how he spent a rather long time in a house hosting potential converts (like the one at Alençon). During the days leading up to the abjuration ritual, he was catechized ("l'on me fit passer en revue tous les dogmes pour triompher de ma nouvelle docilité"). At last, "suffisamment instruit et suffisamment disposé au gré de mes maîtres," he processed to the church, dressed in the grey robe with white trim worn on such occasions. The priest was prepared to have him "recevoir les accessoires du baptême, quoi qu'on ne me rebaptisât pas réellement: mais comme ce sont à peu près les mêmes cérémonies, cela sert à persuader au peuple que les protestants ne sont pas chrétiens." (He was correct: the materials for a baptism were kept close at hand, because church ceremoniale permitted a priest to re-baptize the convert if he had the least reason to think that the original baptism might have been inefficacious.)

Rousseau was also correct about the similarities between his late-eighteenth-century abjuration and that of Henri IV in 1593. Henri began by withdrawing to Saint-Denis, where he spent some time in retreat and was catechized. On the day of his abjuration, he processed to the abbey church. To show his submission, he wore white and black, with no royal ornaments beyond his sword. The noble laymen who accompanied him (as Mme de Guise accompanied Mlle Gouvernet) were likewise very modestly dressed. At the church door, Henri knelt and was questioned by the officiating prelate. There he recited his abjuration and the Profession of Faith, so that the crowd could hear him. He was then escorted into the church and led to the high altar where, holding a Bible, he swore to live and die a Catholic. Having kissed the altar, he withdrew to a confessional for the sacrament of Confession. A high mass followed, during which he was administered the sacrament of Communion. (28)

Mlle Gouvernet's abjuration doubtlessly followed the same sequence of events. We know that she had withdrawn to a "retreat," and that she was catechized by Father de la Barre. Wearing simple white or grey garments, she would have processed from the Palais d'Orléans to the Novitiate, situated five or six streets away. Mme de Guise perhaps led the procession. At the church door the convert would have been questioned by the officiating priest, vested in surplice and purple stole. After this she would have recited the Profession of Faith stipulated by the ceremoniale of Paris for the "absolution of heretics":

With firm faith I (name) believe and profess each and all the articles contained in the Symbol of Faith used by the Holy Roman Church, that is: I believe in one God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and all things visible and invisible: and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, ... who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried .... (29)

This recitation of the Nicene Creed was followed by vows to embrace the Tradition of the Catholic Church, the Scriptures as interpreted by the Church, the seven Sacraments and the other ceremonies of the Church, indulgences, the existence of Purgatory, and so forth. The ceremony ended with a vow of fidelity, pronounced with the convert's hand on the open Bible. (30)

At some point in the ceremony, Charpentier's first work honoring St. Cecilia was performed. Like Mme de Guise, the Cecilia who is depicted in In honorem Caeciliae, Valerii et Tiburtij canticum converts others by the gentle force of reason. The musicians probably were concealed in the large balcony just inside the entrance door. The two women singers and the man with a bass voice, as well as the two treble instruments and continuo, almost certainly were Guise household musicians (I call this group the Guise "Core Trio"). Charpentier had begun composing for the Core Trio earlier that year, 1676, and he would continue to write for this small ensemble until he left the Hôtel de Guise in 1687.

I have gone into the details of this service at length, because the libretto of this canticum, which presents only tableaux 1, 2 and 3 from the Legenda, has as its principal focus the abjuration of a false religion in favor of a true one, and the reception of the sacrament of baptism, which unseals the eyes of the once-blind pagans. Not until Valerian and Tiburtius profess their faith in Jesus Christ, and are baptized, can they see the angel of God. (31)

The libretto is saying, by analogy, that only by professing her faith will Mlle Gouvernet see the divine mysteries to which she previously was blind. (I do not know whether the officiating priest re-baptized her that day.)

The libretto contains a clue that seems to provide corroborating evidence that the piece was written for Mlle Gouvernet's abjuration. That is to say, just before the "suave harmonies" that end the canticum, the three saints sing a paraphrase of the opening lines of the Nicene Creed, or Credo:

Nunc ergo consensu pari juremus in Christi fidem. Te Christum agnoscimus, Te Deum ex Virgine natum et pro nobis passum confitemur. O Christi fidem profitentium caelestes harmonia, O consentus [read: concentus] delectabiles, melodia suavis ... ("Now therefore, together, let us swear our faith in Christ. We recognize Thee, O Christ. Thee we confess, God born of a Virgin and who suffered for us. O celestial harmony of those who confess the faith of Christ. Heavenly harmony, O delectable concerts, O suave melody...")

(To facilitate comparison, here are the lines in the Credo that served as a point of departure for Du Bois' paraphrase of the Profession of Faith: Credo in unum Deum; Patrem omnipotentem, ... Credo in unum Dominum Jesum Christum, Filium Dei ... Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto ex Maria Virgine: et homo factus est. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato, passus et sepultus est....)

I was puzzled at first about the allusions to the Virgin Mary and to Christ's Passion, which I have highlighted in bold type. They were omitted from the second version of Du Bois' libretto and were not used again. This suggests that the allusions were deemed appropriate for the service at the Novitiate (and had presumably been approved or even proposed by the reverend fathers), but that they would be judged inappropriate for the devotional events at which the three subsequent versions of Caecilia Virgo et Martyr were performed.

True, the allusions to the Virgin and to "suffering" are part of the Nicene Creed, and therefore part of the Profession of Faith recited by converts. True, according to the Legenda the "incarnation of our Lord and his passion" were part of Cecilia's "preaching" to Tiburtius. The expressions ex Virgine natum et pro nobis passum nonetheless distract the mind from the story being told about Cecilia, Valerian and Tiburtius, and cause it to focus momentarily on the powerful images of the Annunciation, the Nativity and the Crucifixion. (As far as I can determine, there were no such depictions in the church of the Novitiate; this suggests that Du Bois did not include those allusions in order to evoke the decoration in the church.)

Eventually a possible reason behind the incorporation of ex Virgine natum et pro nobis passum into Du Bois' libretto began to take shape. Mlle Gouvernet's abjuration was brought about by a Jesuit father; it took place in a Jesuit church. The Virgin Mary and Christ's Passion occupied, and continue to occupy a predominant place in Jesuit spirituality. Mlle Gouvernet's time of preparation with Father de la Barre had almost certainly involved the mysteries of the Virgin and the Passion. Hence, I propose, the inclusion of these mysteries in Du Bois' paraphrase of the Profession of Faith.

Cecilia no. 2: Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus: the third panel of a gallery of femmes fortes and saints, November 1677 (H.397)

A year later, Du Bois added a second section for his libretto, so that it now recounted the complete life of St. Cecilia. The new composition was called Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus (H.397). At 908 measures, this piece is only slightly shorter than Judith (1012 measures), but it is noticeably longer than Esther (643 measures).

Compare these figures with Charpentier's two Te Deum's for soloists, choruses and orchestra: H.145 is 794 measures long, and H.146, 720 measures. Or take the more splendid of his masses: H.3 totals 1236 measures, H.4 totals 705, while H.6 (for an event honoring Mr. Mauroy) totals 1502. Or compare the length of the three histoires sacrées about women in the triptych, with the 835 measures of his In obitum, H.409, for a memorial service for the late Queen (to which 804 measures must be added for the overture, the elevation, and the De Profundis).

The three "stories" about strong and courageous women clearly were intended for full-blown devotional events-in-music. Each story approaches in length the masses, the Te Deum's and the memorial services that Charpentier wrote for such prestigious establishments as the Jesuit church of Saint-Louis or the "Grandes Carmelites."

Hence my hypothesis that Judith (H.391), Esther (H.396) and Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus (H.397) were commissioned for performances at the Theatine church of Sainte-Anne-la-Royale, and that the three works belong to a musical gallery depicting strong and devout women, a gallery not unlike the Gallerie that Father Le Moyne had dedicated to Mme de Guise's late grandmother, protectress of Sainte-Anne-la-Royal. (Mme de Guise had acquired a chapel at Sainte-Anne in 1675.)

For these reasons, I think that, in late September 1675, it was Mme de Guise — rather than Mlle de Guise — who sponsored an event that recounted Judith's courage and who honored Esther in late September or early October 1677. Roughly two months after Esther, November 1677, came H.396, the story of Cecilia's life and death. At that point the creation of this musical "gallery" came to a halt, although it cannot be ruled out that some of the works were reused by hired musicians prior to 1684, when the expanded Guise ensemble began to perform. (Do repeated performances explain why, circa 1683-1685, Charpentier recopied this version of Caecilia Virgo et Martyr? Had notebooks 19 and 20 become shabby, as a result of repeated performances?)

I have found nothing to explain why no musical portrait of a femme forte or a heroic saint was presented in the fall of 1676. Or perhaps it was? Did In honorem Caeciliae, Valerani et Tiburtij canticum serve as a new, albeit brief panel in Mme de Guise's on-going musical gallery?

Be that as it may, in Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus the libretto used for the abjuration at the Novitate a year earlier, became Part 1; everything in Part 2 was new. This does not mean that the verbal tableaux about the wreath-bearing angel, the conversions and baptisms and the professions of faith were given short shrift in this expanded version. No indeed: Part 1 of the new work is approximately 100 measures longer than it was in the canticum. As a result, one-third of the new composition is devoted to tableaux 1, 2 and 3, and the other two-thirds depicts tableaux 4 through 7. In sum, the old focus on conversion and baptism remained as strong as before; but now it was completed and strengthened by the depiction of Cecilia's martyrdom.

Throughout this story, as in the canticum for the Novitiate, Cecilia is the gentle voice of reason as she converts Valerian and Tiburtius. In her interactions with Turcius Almachius, prefect of Rome, she likewise reasons calmly:

"To worship gods ... is folly pure. No, no, I'll not make sacrifice to thy false god. ... I fear not thy instruments of pain, thy dire torments: ... if I endure these pains for Christ they shall be sweet and dear to me. ... Therein shall Christ send me sweet refreshing. ... Here I am Jesu ..."

In other words, Cecilia personifies the tolerant approach that Louis XIV had been favoring for over a decade.

Almachius, by contrast, thunders as he threatens to win Cecilia back to paganism by force:

"Most murderously thou hast led thy husband and his brother astray, o thou that worshipest mere fancies and wouldest still deceive ... Make thy sacrifice to Jove, or I shall send thee to thy death ... I'll cast thee alive into the burning, fiery furnace! If thou doest scape the searing flames, the sword thou'lt not avoid.... Executioners, ho! make haste! Take this wretch and torture her to death!"

In short, Du Bois' expanded libretto about Cecilia portrays a saintly woman of the second century who can be paralleled with the devout women who, by creating houses for New Catholics, were carrying out Louis XIV's program, and who were accomplishing this mission according to the gentle guidelines that the King preferred at the time.

As I pointed out in my discussion of the canticum performed at the Novitiate, the most noteworthy difference between the text of H.394 and Part 1 of this expanded version, involves the Profession of Faith as paraphrased by M. Du Bois. You will recall that the libretto used at the Jesuit Noviate a year earlier had read: Nunc ergo consensu pari juremus in Christi fidem. Te Christum agnoscimus, Te Deum ex Virgine natum et pro nobis passum confitemur.... ("Now therefore, together, let us swear our faith in Christ. We recognize Thee, O Christ. Thee we confess, God born of a Virgin and who suffered for us....") In this new version, ex Virgine natum et pro nobis passum have been deleted. The Profession of Faith now reads: Te Christum agnosco, te Deum omnipotentem confiteor, Nunc ergo, unanimes juremus in Christe fidem, "I recognize thee, O Christ; Thee I confess, almighty God! Now therefore, as one, we swear our faith in Christ." This deletion of what I take to be Jesuit imagery strongly suggests that Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus was intended for a different venue.

Note that the libretto states unambiguously that Part 1 concluded with a paraphrase of the Profession of Faith recited by converts. That is to say, Part 2 begins with these words: Cum autem Valerani et Tiburti confessionem intellexisset Tyrannus morte crudelissima damnavit eos, "And when the Tyrant heard the tidings of that confession of Valerianus and Tibertius ..."

Here I will digress briefly, prompted by the paper that Shirley Thompson presented at a colloque on Charpentier's oratorios held at Royaumont in May 2013. She pointed out that in H.397 the libretto reads "confessionem," but that in H.413, it reads "conversionem." In due time I will attempt to explain why, between 1677 and 1684, "confession of faith" (confessionem) was transformed into "a change in beliefs" (conversionem). But for the moment, let us see what confession and "confession of faith" meant to a seventeenth-century Frenchman.

According to the Dictionary of the French Academy, confession de foi denoted a "declaration, an exposition made orally or in writing of the faith one professes." The word is almost synonymous with "profession of faith," but there is a significant difference between a "confession" and a "profession." "Faire une profession de foy," says the dictionary, "means making a public (32) declaration of one's faith and of the feelings one considers orthodox in the religion to which one belongs." (33) In other words, the difference between a confession and a profession lies in the fact that the confession can be private, but the profession must be public. At the end of Part 1, Valerian and Tiburtius did in fact declare their faith privately -- which, of course, explains why Almachius did not learn about it immediately. That is, the Legenda says that Valerian's vision took place outside the city, near the tombs along the Appian Way, and that he declared his faith to an old man he saw in a vision. Monsieur Du Bois clearly was paying close attention to the details provided by the Legenda. He knew the difference between confessio, confessionem and professio, professionem, and the Golden Legend told him that confessionem was the better word. This is an excellent example of the theological and dogmatic rigor prevailing in learned circles in late-seventeenth-century France. (34)

Cecilia no. 3: Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.413) returns in November 1684

After a hiatus of seven years, M. Du Bois' libretto was put back into service: in the autumn of 1684 a new Caecilia Virgo et Martyr was commissioned. This time the impetus appears to have come from Mlle Marie de Lorraine de Guise, whose expanded musical ensemble (the Great Guise Music) had begun performing only a few months earlier.

The royal position on tolerating the R.P.R. had evolved since the relative calm of 1676 and 1677, when Huguenots were primarily being confronted by legal chicanery aimed at whittling away the rights granted them in 1598 by the Edict of Nantes.

But now, in the early 1680s, the mood was changing. Gentleness was no longer the sole approach employed by the royal government to bring about abjurations. Resort to physical force loomed on the horizon: in 1681 soldiers (dragonnades) had been used in the province of Poitou to bring Huguenots back into the fold.

The next year, 1682, was marked by the Assembly of the Clergy, which met from February through July. Gabriel de Roquette, bishop of Autun (Mlle de Guise's "Tartuffe" and M. du Bois' crony) was one of the delegates. Repression increased: 1682, 1683 and 1684 saw the forced closing of at least seventy R.P.R. temples, plus the famous Academy of Saumur.

Before disbanding, the Assembly of the Clergy issued several long letters and memoranda concerning the Protestant problem. The delegates stated unequivocally that they wanted to "dissipate the clouds of heresy by the light of truth." (35) Indeed, the Assembly "resolved to use no threats, ... but to attack [Huguenots] by pressing exhortations, by holy desires, and by urgent prayers, to engage them, by these paths of gentleness, to reconcile with us promptly." (36) As François Harlay, archbishop of Paris, argued: "By observing a conduct that conforms more [une conduite plus conforme] to pastoral charity and to the tenderness of our mother the Church, by paternal warnings we will call back [into the fold] our brothers who have strayed." (37) (Une conduite plus conforme: we will see M. Du Bois use that very expression in late 1685, as the title of book published at Harlay's request.)

At the Assembly, "conversion" was the byword. For example, in a letter addressed to members of the So-called Reformed (Huguenot) Church, the assembled Catholic clergy (and Roquette and Harlay) sent a notice to Huguenots. Calling them "our dear brothers" (as in Tiburtius!) the prelates urged them "to convert"; but in the next breath, the clergy warned of the "malheurs incomparablement plus épouvantables et plus funestes" that would descend upon the Huguenots if they persisted in their "revolt" and their "schism." The king sent the letter to all the provincial intendants, ordering that it be read aloud in the presence of the local officials, pastors and elders. (The pastors and elders almost unanimously replied that they respected the King and the delegates to the Assembly, but did not believe that they had any authority over the beliefs of the R.P.R.) The Assembly also drew up a memorandum about the different methods for "converting" the Huguenots (among them was the gentle approach that St. Augustine had taken with the Donatists). (38)

At the Hôtel de Guise, where Bishop Roquette was a frequent visitor and where M. Du Bois was in the throes of finishing and publishing his translation of St. Augustine's letters (including several letters about bringing the Donatists back into the fold), there must have been much talk about "conversion."

In November 1682 (and perhaps again in 1683), did these debates about the force of reason versus physical force perhaps prompt Mlle de Guise and her entourage to revive In honorem Caeciliae, Valerii et Tiburtij (H.394)? The canticum almost certainly had been written for and performed by the Guise Core Trio back in 1676. Since this in-house ensemble was still active, such a possibility should not be ruled out. One can only hypothesize about, and therefore only guess at just how intense were Mlle de Guise's (and presumably Mme de Guise's) feelings about gentle and patient persuasion versus physical force. I personally doubt that, at that conjuncture, either of the princesses would have hired the large musical ensemble required for Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus (H.397). I am not thinking of financial reasons, because neither women lacked money. I am thinking of personal reasons. Mlle de Guise's sister, the abbess of Montmartre, was in extremely poor health during the autumn of 1682 and died in late December. Mlle de Guise therefore spent much of 1683 not only grieving but also pressuring the different powers that be to obtain bulls for the new abbess (a young Lorraine of the Harcourt branch). Then, in late July, the queen's death sent everyone into official mourning. As for Mme de Guise, she now tended to spend most of each fall and winter at the royal court, coming to Paris only for special events. (I have found no evidence of her presence in Paris in November 1683.)

Be that as it may, in November 1684 came a new version of Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.413). This piece was written for the newly created Great Guise Music, which had begun performing during the spring or summer of that year, 1684. (Is it merely a coincidence that the first piece for Cecilia was created only a few months after the Guise Core Trio began singing regularly, and that this third work for Cecilia was created only a few months after the Great Guise Music began to perform?)

The lapse of seven years brought virtually no changes in the libretto. That this work reuses Du Bois' earlier libretto for Caecilia Virgo et Martyr octo vocibus (H.397), strongly suggests that the Guise position on how best to win over Huguenots had not changed. I counted only five changes. Four of these changes involve single words added or deleted. The fifth change is the conversionem that, as Shirley Thompson pointed out, replaces confessionem. Viewed in the political-religious context that I just sketched, this particular modification does not mystify: it echoes the vocabulary being employed by delegates to the recent Assembly of the Clergy — among them, Gabriel de Roquette.

Before moving on to the

next Caecilia, I think it wise to summarize both my working hypotheses

and the facts I have been able to pull together. We do not know which of

the two Guise princesses commissioned H.413 in the fall of 1684. It may

well have been a joint venture. Nor do we know at which of the several

possible venues the work was performed. One seemingly insignificant

modification (conversionem) to Du Bois' eight year-old libretto strongly

suggests that the new Caecilia was inspired by discussions, pro and con,

about the position taken by the French clergy during the Assembly of

1682. It seems safe for us to speculate that the time-lag between the

final report of the Assembly in July 1682 and the performance of this

new Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.413) can be explained by the fact that

the Great Guise Music, with its numerous young adolescent singers, did

not yet exist in November 1682, and that although the young people may

well have entered Mlle de Guise's service at some point in 1683 and

began training with M. de Montailly, their singing coach, performances

before even a small public were probably out of the question until

mid-1684. Then too, in late 1683 Mlle de Guise had more pressing issues

to resolve than "conversions."

Cecilia no. 4: The Assembly of the Clergy, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, and the creation of yet another Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.415), for November 1685

Note:Our understanding of the circumstances surrounding the writing of H.415 depends on verbal clues scattered in several texts with which M. Du Bois was acquainted. In this section, these clues are shown in bold-face type.

A new Assembly of the Clergy began meeting in late May of 1685. This time, Gabriel de Roquette was not a delegate, but Archbishop Harlay was, and he would play a major role in the Assembly's debates.

Speaking for the king, Harlay told the delegates of Louis XIV's intention to send missionaries into the provinces to convert Huguenots, and of the plan to provide pensions to pastors who converted. Harlay himself "ordonna aux curés de [Paris] d’envoyer leurs ecclésiastiques chez les Huguenots de leurs paroisses pour tâcher de les ramener." As sessions continued, numerous royal decrees were being issued against the R.P.R. The concluding speech by Nicolas Colbert, coadjutor of Rouen (it was ghost-written by Jean Racine!) expressed the Clergy's hope for a gentle extermination of the heresy: "By winning the hearts of the heretics, you [Louis XIV] check the obstinacy of their minds: by your good deeds you combat their hardening, and they perhaps never would have returned to the bosom of the Church by any way other than the flower-strewn path that you have opened for them." (39) (Hm, "flowers"!)

That summer, the dragonnades resumed on a large scale. Louis XIV had made up his mind to end things quickly. By August 1685 he had decided to revoke the Edict of Nantes. The Revocation was issued on October 18, at Fontainebleau. It gave pastors two weeks to abjure or be banished from the kingdom. Lay people were forbidden to emigrate; if they attempted to do so, they would be sent to the galleys, a virtual death sentence. Wellborn women and children were sent to houses for New Converts or to convents, where they were forced to receive instruction in Catholic doctrine.

On October 29, the following message from the king went out to the provincial intendants: "After so much happy success with which it has pleased God to crown the continued application and indefatigable cares of the King for the conversion of his subjects, you may well understand that his Majesty has nothing closer to his heart than the completion of this work, so agreeable to God and to his Majesty. ... The King believes that nothing could be better than to have those who are still in error be instructed by the new converts to our religion; they should be most capable of drawing others to the light." (40)

This chronology is important for our understanding of H.415, because on November 12, 1685, a scant two weeks after the king's missive to his intendants, and only four weeks after the Revocation, in a brief post-script the Tuscan resident in Paris told his colleagues in Florence about two related manuscripts that would soon be on their way to the Grand Duke. There was a "discourse" by M. Du Bois, and there was a "libretto," also by Du Bois:

"[Attached] is the discourse on the two letters of Saint Augustine translated by M. de Bois, chapel master to Mlle de Guise, by order of Monsignor [the archbishop] of Paris. I will send his libretto for our Italian musicians." (Il discorso sopra le 2 lettere di S. Agostino lo had tradotte M. de Bois [sic], maestro di capelle di Madlle di Guisa, d'ordine di Monsignor de Parigi. Manderó il libretto [sui per?]i musici nostri d'Italia.) (41)

Brief though it is, this post-script provides a precious insight into the sort of time-table with which Du Bois and Charpentier had to cope when they prepared a major musical event. That is, by November 12, Du Bois was able to give the Florentine residents a fair copy of the introduction to his La Conformité de la Conduite de l'Eglise de France pour ramener les Protestans. (La Conformité would be available in print in 1686; Du Bois' name does not appear on either the title page or the privilège, but everyone who counted knew who had written the introduction.) On the other hand, the libretto would have to be sent at a later date. In other words, some ten days before the planned performance, Charpentier apparently was still working on his score for H.415.

Let us look at the two writings that Du Bois was proudly sending to the Duke of Florence, starting with the "libretto" and moving on to the "discourse."

— The libretto

One year after Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.413), Charpentier copied into his notebooks yet another version of that libretto. Once again, he named it Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.415). This work, too, was written for the Great Guise Music; and Charpentier sang the role of Tiburtius, as he had in version H.413.

The libretto begins like its predecessors; but then some new lines about Tiburtius and the angel were inserted into the existing text. This emendation comes just after the lines where the mystified Tiburtius exclaims "Oh, sweet, oh marvellous scent, unseasonable, who gave you these fair blooms?" (O suavis, o mirus pro tempestate odor. Quis dedit vobis flosculos istos); and where Cecilia and Valerian inform him that it was "God's angel, who guardeth us" (Angelus Dei qui custodit nos) and insist that what they are telling him is "a wonder aye, and true (Et mira et vera).

Tiburtius asks to see the angel's face. The angel complies and, dazzled by the sight, Tiburtius is converted:

"May the angel of God show me his face, and I will proclaim the Holy Name of Christ and Jove's false power. ... O ineffable splendor, intolerable brightness, as beautiful as it is terrifying." (Ostendat mihi faciem suam angelus dei, et Christi sanctum nomen et Jovis falsum numen publicabo. ... O splendor ineffabilis, fulgor intolerabilis, quam pulcher quam terribilis.)

(The mere thought of conducting Mlle de Guise's musicians could make Du Bois ecstatic. (42) Imagine, then, his joy at inventing these lines, with their repetitious poetic rhythms, their rhymes, and their rhetorical oppositions: ... Christi sanctum nomen et Jovis falsum numen, and O splendor ineffabilis, fulgor intolerabilis, quam pulcher quam terribilis ....)

Apparently

alluding to the pagans whom Tiburtius will be going out to convert, the

angel says:

"O Tiburtius, let them not tremble with fear, but

let

them catch fire in their innermost heart, to profess their faith in

Christ, for which you will earn a crown of glory. Fly, fly to the

purifying fountains ... They will make your old Adam a new man." (O Tiburti, ne pavescant prae timore sed ardescant intima praecordiam

Christi fidem profiteri ex quo possis tu mereri coronari gloria. Vola,

vola fontes ad lustrales ... a te possunt pellere rore sacro cum lavatus

eris homo renovatus ex Adamo vetere.)

The lines about the angel that M. Du Bois inserted into the earlier libretto emphasize the importance of seeing: one's eyes must be unsealed if one wishes to convert and to understand the mysteries taught by the Catholic Church. He also inserts a statement to the effect that the convert whose eyes are thus uncovered, can spread the word to others and, casting off Adam's Original Sin, all these converts, washed in the "purifying fountains," can be "new men."

At that point, the libretto returns to the earlier version: Incertus vix credo, quod certum agnoscis...., and continues unchanged to the end of Part 1.

Du Bois' emendation to the libretto reflects the position taken by Louis XIV only a few months earlier (quoted above): "... The King believes that nothing could be better than to have those who are still in error be instructed by the new converts to our religion; they should be most capable of drawing others to the light."

The text that Du Bois inserted about kindling a fire in the hearts of other pagans suggests that Mlle de Guise, Mme de Guise, and their entourage had adopted the king's position about the role to be played by New Catholics in converting their brothers and sisters. This in turn suggests that the women were prepared to promote the conversion of women and girls by confining them to convents where they would be inculcated with the tenets of Catholicism. That is, the princesses were prepared to do all they could to make these young women "see the light," so to speak.

The light: that brings us to the "discourse" by M. Du Bois.

— The discourse

The Tuscan resident's post-script, quoted earlier, revealed that François Harlay de Chanvallon, archbishop of Paris, had asked M. Du Bois to write a "discourse." Du Bois had complied. Was Du Bois merely Harlay's ghost-writer? Or was he expressing his own thoughts and those of his protectress, Mlle de Guise? The answer to these questions seems to be: "Both of the above." That is to say, even though Du Bois' name did not appear on the title page of the "discourse," it was public knowledge that he had "belonged" to Mlle de Guise for two decades, and that the two letters by Augustine had first appeared in his multi-volume translation of the saint's Lettres, published in 1684 and dedicated to Mlle de Guise. The position taken by Du Bois in this "discourse" can therefore be seen as inseparable from the positions taken by Mlle de Guise and the Archbishop of Paris — and probably Mme de Guise as well.

For a title, Du Bois was inspired by a phrase that Harlay had employed a few months earlier, when addressing the Assembly of the Clergy of 1685: ... "Une conduite plus conforme." Hence Du Bois' title: La Conformité de la Conduite de l'Eglise de France pour ramener les Protestans: avec celle de l'Eglise d'Afrique pour ramener les Donatistes à l'Eglise Catholique. The publication consists of an thirty-two page introduction (the "discourse"), plus two long letters by St. Augustine that had appeared in Du Bois' edition of the saint's Lettres in 1684.

Written during the weeks that immediately preceded and followed the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, the "discourse" draws a parallel between Augustine's approach to converting the Donatists, and the French Monarchy's current policy for converting Huguenots. Du Bois explained why he was publishing these two letters under a new title. One could not expect "everyone" to purchase the expensive volumes he had produced in 1684; "people who are highly trusted by the king on matters involving the Church" therefore deemed it "appropriate to publish a few of these letters":

Mais comme il seroit difficile de mettre entre les mains de tout le monde le corps entier des Lettres de saint Augustin, ceux qui ont la principale part à la confiance du Roy, sur ce qui regarde les affaires de l'Eglise, et à la conduite du grand dessein qui s'execute si heureusement, ont jugé à propos de faire imprimer à part quelques-unes de ces Lettres où l'on voit le mieux l'Histoire de ce que l'Eglise d'Afrique faisoit autrefois, sous l'authorité des Empereurs, pour faire rentrer dans la Communion Catholique ceux qui s'en étoient separez.

La Conformité exists online as a free Google Book, so I will resist the temptation to quote from it copiously. It is nonetheless essential to quote a few passages that reveal the issues going through Du Bois' mind that November. The following excerpts suggest the extent to which these thoughts made an imprint on the imagery of the newly revised libretto for Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H.415).

At least seven times, Du Bois talks of "seeing" the "truth":

Il faut quelque chose qui applique les esprits à la verité, et qui les oblige à vouloir voir ce qu'il est clair que la seule prevention leur cache. ...; Ce n'est que faute de remonter jusques là [Luther] que leurs yeux demeurent fermez à la verité. ...; Le pourrions-nous croire, encore une fois, si nous ne le voyions de nos yeux. ...; [les hérétiques] peuvent-ils s'empecher de voir ...; Il n'en faut pas davantage pour faire ouvrir les yeux à quiconque voudra y penser de sang froid. ... car il faut quelque chose de fort pour lever le voile qui empêche qu'on voye la verité. (43)

Here Du Bois is echoing the delegates (among them Roquette and Harlay) to the Assembly of the Clergy of 1682, which, we will recall, had expressed its desire to "dissipate the clouds of heresy by the light of truth." He is echoing the king's assertion of 1685 that nothing could be better than to have those who are still in error be instructed by the new converts to our religion; they should be most capable of drawing others to the light."

It doubtlessly was with this idea of light and truth turning in his head, that Du Bois added to the libretto the scene where Tiburtius, in a dazzling, brilliant vision, is at last able to see God's angel. Gone is the "fog" (caliginem) that had blinded his pagan soul. He now knows the truth of Jesus Christ, as contrasted with the "false" gods of paganism.

In like manner, it appears that several sentences from one of the letters published in La Conformité led Du Bois to add to the libretto the material about casting off Adam's sins by baptism: "... le Baptême efface absolument toutes les taches de nos pechez passez, ..."; and "... nous traînons encore les restes de la mortalité que nous tenons d'Adam ...." (44)

A look at Du Bois' choice of words in other passages of the discourse reveals the extent to which the "méthode pacifique" praised by the Assembly of the Clergy in 1682 had virtually disappeared by 1685. In its place we find "la force de la verité." As a loyal subject and a Catholic, throughout his discourse Du Bois espouses the position that Louis XIV expected of every devout Catholic subject:

On y verra que saint Augustin luy même avoit été d'avis qu'il ne falloit employer que la force de la verité pour ramener les heretiques; ... Ce sont des brebis errantes, mais comme elles portent la marque de Jesus-Christ, les Pasteurs legitimes [that is, Catholique priests] ont droit de mettre la main sur elles pour les faire rentrer dans la bergerie, et employer même la verge pour cela, quand l'entêtement, l'accoûtumance, ou la paresse empechent que les autres moyens ne fassent leur effet.

... il faut quelque chose qui applique les esprits à la verité, & qui les oblige de vouloir voir ce qu'il est clair que la seule prevention leur cache. ... et ceux qui se trouvent engagez dans l'heresie par le malheur de leur naissance peuvent-ils s'empescher de voir par là quelle est la force de l'accoûtumance et de la prévention?

Voila donc à quoy il faut ramener nos Prétendus Reformez, et à quoy un peu de severité les fait penser: car il faut quelque chose de fort pour suspendre les impressions de l'accoutumance, et pour lever le voile qui empêche qu'on ne voye la verité. C'est sur ce principe qu'on agit presentement, comme c'est sur celuy-là même que l'Eglise d'Afrique agissoit du tems de saint Augustin.

Qu'ils jugent donc aussi des choses non par leur disposition presente, mais par celle où ils se trouveront lors qu'ils auront reconnu la verité, par le moyen de la severité salutaire qui leur y fait faire attention ... ; et que l'amour de la santé leur fasse prendre au gré l'amertume du brevage qui la leur procure. Qu'ils considerent quel bien c'est que la reunion; quel bon-heur ce sera pour ce Royaume de se revoir dans le même état où il étoit avant la naissance de l'Heresie..

.

[The Church only uses] la crainte .... que pour faire que leur cœur s'ouvre à l'instruction qu'elle leur presente en même temps qu'elle leve la verge sur elles; et ce n'est que de l'instruction qu'elle attend ce qu'elle desire, qui est de les voir revenir à elle par la connoissance et amour de la verité. ... Car elle est bien éloigné de vouloir que ce soit en trahissant leur conscience qu'ils passent dans sa Communion. (45)

Let us note, in passing, the emphasis upon "opening the hearts" of converts to the instruction they are being given. (46) The same idea was inserted into the libretto, when the angel told Tibertius: "but let them catch fire in their innermost heart, to profess their faith in Christ...."

Du Bois ended his "discourse with a prayer of sorts: "Plaise à la misericorde de Dieu d'achever ce grand ouvrage; et de benir des intentions aussi pures que sont celles de son Eglise, dans l'envie qu'elle a de regagner à Jesus-Christ un si grand nombre d'ames, et de les garentir de la mort."

Note how consistently Du Bois states the position being taken by the Church (underlined in the above quotes): Something "strong" must be done. This is "the principle currently being acted upon." And what a joy it will be for the kingdom to see the heretics united with the Catholic church, which wants them to return when their eyes have been sincerely opened to the truth.

In his "discourse," Mlle de Guise's protégé was allowing the fruit of his intellectual labors, and the mastery of his quill pen, to speak on behalf of the policy of "force," "fear" and "severity" now being espoused by the Monarchy and the Church.

It was, however, one thing to take that position in print, under the protection of the Archbishop of Paris. It was another thing to weave that fear, force and severity into a libretto. Back in 1677, the "cabal of Isis," had led to the disgrace of Lully's librettist, Philippe Quinault. A faction at court had accused Quinault of ridiculing the king's mistresses, and therefore the king himself. As Jérôme de la Gorce has observed, this was too serious a deed to go unpunished; the blame fell on the author of the libretto, who spent two years in disgrace. (47)

We saw that, in Parts 2 of H.397 and H.413, the "tyrant Almachius" sends Christian converts to their deaths. He rails against Cecilia and, when threats do not win her over, he summons the executioner. Although the word "tyrant" was not always employed, Louis XIV's arbitrary treatment of the Huguenots was already being criticized by numerous European rulers and political thinkers. (48)

Who, in November 1685, would be foolhardy enough to present a work that might lead to the librettist's being accused of drawing a parallel between the "tyrant" Almachius and King Louis XIV? Especially when the librettist was known to have once been close to some other heretics who were causing the Monarchy endless problems: the Jansenists around Pascal and at Port-Royal-des-Champs.

Indeed, in November 1685 there clearly was some indecision at the Hôtel de Guise about the length of the new version work: should it consist of two parts, as it had in the past? But Part 2 could not exist without its nasty villain, "Almachius the tyrant" (Almachius tyrannus), who gleefully punished people who refused to convert to his preferred religion. The implicit parallel with Louis XIV had to be avoided at all costs. Would Part 1 perhaps suffice, as it had in the past?

In the end, the new piece retained the title Caecilia Virgo et Martyr but the libretto shrank to virtually the same text as in 1676 (H.394). To record this decision, Charpentier blacked out his allusions to "Part 1" and "Part 2" and wrote Finis at the bottom of the page. (49)

Cecilia no. 5:A Prologue for "singing sisters" to be added to the fourth Caecilia Virgo et Martyr (H. 415), November 1686

Within days of the Revocation, virtually all the Huguenots of Alençon had fled: "Lorsque les troupes arrivèrent à Alençon le 14 novembre, elles trouvèrent les maisons vides de meubles ou d'habitants." Indeed, a newsletter noted that:

Tout Alançon [sic] est catholique. L’Intendant fit assembler tous ceux de la Religion afin de sçavoir leurs résolutions et leur apprendre la volonté du Roy. Ils dirent tous qu’il estoient en résolution de mourir dans la Religion où ils estoient nez. L’Intendant voïant leur dernière volonté dit tout haut à un des ses Hacquetons qu’il allast donc querir les cuirassiers. Ce mot les epouvanta si fort qu'ils crierent tous d’une voix, qu’ils estoient catholiques. Les Eglises demeurent ouvertes jour et nuit pour les recevoir. L’intendant a mandé que dans 4 jours il ne resteroit pas 6 Religionnaires. (50)

In Paris, during the weeks and months that followed the Revocation, women and children were brought forcibly to houses for New Catholics or to convents, there to be instructed in Catholic dogma. By early 1686, a Parisian newsletter stated that few Huguenots remained in the diocese of Paris, and noted that young girls of high rank had been placed in convents, to be converted. (51)

Mlle de Guise was personally involved in this mission to convert Parisian Huguenots. A newsletter dated December 7, 1687, alludes to a New Catholic who had been forcibly detained at the abbey of Montmartre and who had fled to Holland to join her parents. That the girl was at Montmartre, was owing to Mlle de Guise: "C'est Mlle de Guise qui avoit mis à Monmartre cette nouvelle convertie qui s'est echapée deguisée en servante pour aller rejoindre ses parens en Hollande" (52) These forced conversions presumably had been going on throughout 1686 and into 1687. The girl who managed to escape almost certainly was not the only Huguenot being confined at Montmartre!