The

Ranums'

The

Ranums'

Panat Times

Volume 1, redone Dec. 2014

Fêtes at the Farnese Palace,1666-1668

Shortly after Mardi Gras of 1665, Christina of Sweden began preparing for a journey to Hamburg. Despite the fact that she planned to be gone for some time, she was making plans to improve the Riario Palace, where she and her householders had been living since the summer of 1663. She wanted an "oratoire" and an apartment for the monk who would supervise this devotional place. She also planned for a theater in which to "recite comedies." Oliva, the Jesuit general, was not very happy about the latter project.(1)

Escorted out the city gates by a cluster of cardinals, the Queen left Rome on May 22, 1666, with plans to stop at Loreto along the way. One month later, June 24, the new French ambassador, Charles d'Albert d'Ailly, Duc de Chaulnes, made his official entry into Rome. His coach was preceded by a large number of pages followed by two splendidly mounted scudieri.

Having paid the obligatory visits to all the cardinals, the Ambassador ― who was determined to stun the Romans by a magnificence truly worthy of the monarch he was serving was quickly caught up in the annual cycle of entertainments. The first was the Feast of St Louis, August 25. On that very hot day, the church facade was "ornée de tapisseries." In addition, "les trompetes faisoient connoistre à Mrs les Cardinaux en arrivant la joye qu'on avoit de le recevoir." The entire church, up to the vaults, was hung in "damas chamaré de galon d'or, et le coeur [choeur] de velours rouge avec des crespines d'or."

These decorations had been the work of Abbé Bourlemont, a member of the Rota who had stayed on at the Farnese Palace as attaché, to maintain diplomatic presence after Ambassador Créqui left Rome owing to the Corsican Affair. It is not clear who organized the music that day, which consisted of "6 choeurs de musique des meilleures voix de Rome." During the meal that followed ― it was a gift from Cardinal Antonio Barberini ― there was "un concert de voix et d'instrumens qui vint sur les onze heures du soir dans la place Farnese, dessous le balcon, dans deux chars fort beaux. ... La musique y fut fort belle, les musiciens furent satisfaits des applaudissemens et des traitemens qu'on leur fit."(2) The Ambassador admitted to Louis XIV his surprise when a number of elderly and ill prelates excused themselves from coming that day. But, he continued, wittily:

L'on fut fort surpris d'y en voir venir qui à peine pouvoient marcher. Pour moy, Sir, je creus que deux ou trois vouloient mourir au lict d'honneur, c'est à dire rendre l'ame au pied de l'autel: ce qui fit conclure à tout le monde que la devotion du saint les faisoient moins marcher que le respect pour V.M. et que Louis qui est dans le ciel, n'avoit pas tant de part à leur zèle, que celuy qui regne sur la terre.(3)

By mid-January 1667, Chaulnes and his staff were preoccupied with preparations for Mardi Gras. Like the more powerful cardinals, the Ambassador had been obliged to vie for performers. He was overjoyed at being able to snap up the "troop" of "actors" who had performed for Queen Christina in 1666:

Il y a eu une grande affaire entre Made la duchesse de Mantoue et Mr le Cardinal Chigi, laquelle vouloit empescher qu'une troupe de comediens que ledit Cardinal avoit mandé ne vint icy: mais comme il est fort en ces sortes de negotiations, il a remporté la victoire. Il y a huit jours qu'ils jouent, mais je n'y ay pas encore esté, et en mon particulier j'auray une troupe de Rome qui joueront seulement dans mon palais, ayant creu que ce divertissement chez moy pouvoit aprivoiser le monde, et contribuer au service du Roy: ce sont les mesmes qui jouaient devant la Reyne de Suede.(4)

A Roman source names one of the performers: Maria Vittoria, "cantarina brava comica."(5) In other words, these comédiens, these "actors," were hired for a theatrical involving music. Had Jacques II Dalibert come to the Ambassador's aid, to ensure that the Farnese would not lack outstanding singers and actors?

These divertissements would be held weekly: "Ils [Chaulnes and his wife] donneront toutes les semaines des divertissements au public où tout se passera assurément avec beaucoup de magnificence. L'on va quelquefois à la comedie de la ville où les principaux officiers ... du pape s'y trouvent fort souvent."(6)

The first performance took place in late January. Chaulnes promptly wrote about it to Foreign Minister Lionne in Paris:

Dimanche j'ay donné le divertissement à tout Rome, ayant esté à la comedie publique et laissé la liberté à tout le monde d'entrer à celle que j'ay fay reciter dans ce Palais [Farnese]. J'ay fait dresser le theatre au bout de la galerie haute, par la voute de laquelle le dernier entend aussi bien que le premier, et il y vint plus de cinq ou six cens personnes. L'on joue presque tous les jours, tantost une troupe d'opera, tantost une comedie: et pour conclusion M. le duc de Bracciano en fait concerter une en musique, qui y sera aussi recitée.(7)

This brief paragraph provides some important information: the stage was set up in the painted gallery of the Farnese, famed for its astonishing acoustics; there were daily performances; an "opera" alternated with a comédie, presumably a spoken play that perhaps had musical interludes; Flavio Orsini, Duke of Bracciano, who was on the French payroll — and not Jacques II Dalibert ― was serving as the impresario; and rehearsals were underway for a "comédie en musique" that would be partly sung and partly spoken.

A week later, the Ambassador wrote Louis XIV about these entertainments. The Pope's illness, he reported, had made the season more sober ― hence the importance of the performance being prepared by Bracciano. "L'on recita hier au soir sur un theatre que j'ay fait dresser dans une galerie de ce Palais, une comedie en musique que M. le duc de Bracciano avoit pris le soin de faire concerter depuis quelque temps." Chaulnes had constructed balcons for the princes who were bound to experience "difficulté pour les rangs." He himself was "bien aise de faire prendre ce divertissement sur le sujet de la naissance de Madame [Louis's daughter], ainsy que le marquoit le prologue." Incredibly, 1200 people were squeezed into the gallery:

sans le moindre ambarras, et sans qu'elle ayent eu la moindre peine, et que la Reyne de Suede l'année passée avec douze Suisses et quantité de gentilhommes n'avoit pu empescher que l'on ne tirast l'espée jusque dans son antichambre: ce divertissement plus serieux se continuera tout ce carnaval, estant alternativement meslé de comedies Italiennes, qui sont jouées les autres jours par deux troupes differentes.(8)

In short, some of the comédies were commedie dell'arte ― specifically, two separate plays, each performed by a different troop. On the other hand, there was another sort of comédie, a comédie en musique that celebrated the birth of a French princess in a sober way that would demonstrate how sincerely France regretted the Pope's poor health. Does this silence about the "opera" suggest that it was deemed too cheerful and was cancelled?

But was it cancelled? That very same day, Hugo Maffei, an Italian on the embassy staff, wrote Lionne about the entertainments. For the first time, he said, the Ambassador had la comedia in musicha performed, and it was a veritable success. The recitative was very beautiful, all the actors performed to perfection, the music was by a great virtuoso, Ercole Bernebei, the current chapel master at St Jean Lateran. Berbebei had agreed to write the music because he was eager to call attention to himself, in hopes that he would be named chapel master at Saint-Louis-des-Français. The opera pleased not only the Italians, asserted Maffei, but the French as well. The rich and charming costumes, and the ballets too, were highly praised by everyone. Of special note was the lighting, which took the form of silver-gilt lamps aglitter with hanging crystals.(9)

The overjoyed Ambassador soon announced: "Je me declare pour la musique d'Italie contre celle de France."(10)

A few weeks later, he ordered the ambassadorial staff to improvise another entertainment ― a float not unlike the one with which Jacques II Dalibert purportedly had caught Queen Christina's attention a few years earliers. But on this particular float consisted of "douze sybilles dans un char de triomphe, qui predisoient à la France sous la figure de Pallas relevée beaucoup au-dessus dans un trosne, la destruction de l'Empire Ottoman, ... accompagné de force pages et cavaliers" carrying trumpets. One of the avvisi di Roma gave a very different reading to the iconography of this float:

... est sorti du palais du Seigneur Duc de Chaulnes un char représentant la France guerrière qui invitait les Dames du Tibre, comme tant d'Amazones, à s'unir à elle contre l'Ottoman, tenant sous elle le Croissant de Lune avec eux esclaves, précédé de trompettes, de la Renommée, et d'une grande quantité de masques à cheval en livrées.(11)

As the vehicle moved along the Corso, it was, Chaulnes assured the King, very well received.(12) Another letter identifies some of the participants: Maffei was one of the sibyls; the Italian text was written by Abbé Santis, an employee at the Embassy, and the Italian was by .... Charles Coypeau d'Assoucy!

Je vous envoye le sujet de la mascarade en vers françois et italiens, l'abbé S[an]tis a fait les secondes, et un nommé d'assouci les premiers, ensuite de la mascarade l'on eut la comedie italienne en ce palais, ainsy qu'aujourd'huy de deux troupes differentes, et fort bonnes.(13)

Just a year earlier, Dassoucy had been ingratiating himself at the Riario Palace and had written a poem begging Christina to "admit him to her comédie en musique." Now that Queen Christina was absent, the burlesque poet had not only worked his way into the household of the recently arrived Ambassador, he had dashed to his rescue: "Ces productions ont esté faites à la haste. Il faut les lire sur ce pied," observed Abbé Machault.(14)

In August 1667 the Ambassador entertained the nephews of the new pope, Innocent IX:

Je leur donnay à souper mercredy dernier, et à un autre Parent du Pape; et la curiosité ayant porté plus de deux cens personnes à voir tant cette nouveauté que la manière dont on traitoit à la française, je n'oubliay rien pour les satisfaire, et apres le souper, par les meilleurs concerts de Rome.(15)

We learn from Abbé Santis that the music consisted of "a concert of violins played alternatively with trumpets."(16)

In November of that year, Charles-Maurice Le Tellier, the son of royal minister Michel Le Tellier, arrived in Rome, seeking bulls for the coadjutorship of the archbishopric of Reims. A lodging near the Farnese was made available to him, and during his two months in Rome, he frequently entertained friends there. (There is no evidence for or against the presence of Jacques II Dalibert at Le Tellier's parties, but it seems likely that he was invited, especially because the letter of recommendation to Christina in 1662 had emphasized that Dalibert was a relative of the Le Telliers.) Until his arrest in early December, Dassoucy provided musical entertainment for these parties.(17)

(That same month, a certain "Carpentier" was hired by the Embassy to provide Le Tellier with livery for the servants he had hired. "Carpentier" is, of course, a familiar French name. But "Carpentier" is also the way that Hugo Maffei, the Italian who paid the bill, would have pronounced "Charpentier." Was "Carpentier" actually Marc-Antoine Charpentier?) (18)

Having been promised the bulls, he sought, Le Tellier began talking about returning to France. The Embassy staff was perplexed, for they had hoped to keep him for "tout le Carnaval où l'on esperoit le divertir de quelques comedies en musique." He remained inflexible. Thus, "l'on a mesme donné ordre de presser la representation d'une comedie en musique, pour qu'il la peust voir avant son depart."(19) The sources say nothing more about this "comédie en musique," but one does wonder whether Dassoucy's arrest had something to do with the delay.

Another letter reveals that one of the Ambassador's duties was to find actors and musicians and send them on their way to Paris. For example, Chaulnes kept Lionne informed about an Italian actor possibly Girolamo Cei(20) ― whom Louis XIV wanted at the French court:

Pour finir selon le temps de Carnaval, je vous diray que j'obligeay le comedien italien que S.M. m'a commandé par une lettre de cachet de luy envoyer, de partir avant hier pour aller à Naples où est sa femme, et s'en aller aussytost après en France: une lettre que j'ay reçu encor de M. le Grand Prieur par ordre du Roy sur le mesme sujet m'ayant empesché d'attendre la fin du Carnaval; il n'a jamais voulu partir sans avoir son voyage, Je luy ay donné soixante pistolles, sçavoir trente pour luy et trente pour sa famille qu'il rendra à qui on voudra: je vous envoye les deux billetz: Il a plus d'esprit que Scaramouche, mais il n'a pas le corps tout à fait si bon, et je souhaite qu'il vous fasse rire ....(21)

During this Mardi Gras season, 1668, the new pope and his nephews were in the limelight. The papal family was sponsoring a devotional opera, often called la Comica del Cielo but officially entitled la Conversione di Santa Baldassara, comica spagnola:(22)

L'on recite en musique pendant ces jours gras chez les parens du Pape une pièce de devotion intitulée la Comica del Cielo, que l'on dit avoir esté faite autrefois par Sa Sainteté. La Poesie en est tres delicate et la decoration sur theatre la plus belle et la plus superbe qui se soit veue depuis longtemps à Rome, le Bernin en ayant eu la direction; et fait travailler aux machines et perspectives Pietro Paolo Todesco, un des plus habiles d'Italie en cette profession, et Gasparo Poussin, celebre paysagiste a fait les peintures. ...

Mais la magnificence envers les Spectateurs toutes les fois que l'on a fait cette comedie passe celles qui se sont faites depuis longtemps icy en pareil temps, car non seulement des Dames, Cardinaux, Ambassadeurs, Princes etc trouvent dedans les chambres où ils s'assemblent des superbes collations avec des eaux, sorbets, et tous les rafrichemans les plus exquis, et de plus cette liberalité s'etant [s'etend] encor par toute la salle de la Comedie pendant deus heures que l'on y distribue indifferammant glaces et quantités de bassins de confitures seches, candits et dragées.(23)

One of the Italians at the French Embassy pointed out that some people found the music "lunge e odiosa." Chaulnes attended the "comédie," but it was "deux tiers par politique."(24)

The nepoti not only sponsored la Comica del Cielo, they also had some "pastorales" performed. In addition, they organized "mascarades" — one of them a float pulled by twelve horses and showing a Vesuvius in full eruption. (A drawing of this float by Pierre-Paul Sevin has survived.)(25)

It would be understandable that, in this context, the French embassy might hesitate to invite the public to the "comédie en musique" that had been hastily performed for Abbé le Tellier.

Having convinced Louis XIV that his purse was empty, Chaulnes began preparing to return to Paris once the summer heat had abated. He nonetheless continued to organize events that would enhance France's reputation among the Romans. One of these events was a Te Deum sung at Saint-Louis-des-Français to celebrate the peace agreed at Aix-la-Chapelle on May 2, 1668:

Mr l'Ambassadeur fit chanter mercredy le Te Deum en l'Eglise de Saint Louis où assisterent les Cardinaux factionnaires de France et d'Espagne, et le soir à un beau feu d'artifice qui se fit en la place de Palais Farnaize avec une splendide collation.(26)

A few cardinals came incognito, as did the Spanish ambassador. As usual, the exterior of the church was hung with precious tapestries from the Farnese, The Farnese was also decorated. The embassy staff sent Paris the following account of this lavish event:

[I ly a eu un] feux d'artifice pour la rejouissance de la Paix, le matin [l'Ambassadeur] en fit chanter le Te Deum à St. Louis. ... A une heure de nuit, Mr le Duc de Chaulnes conduisit Mrs les Cardinaux, les Parens du Pape et les Ambassadeurs dans une galerie, où ils trouverent une collation tres magnifique, pendant que Madame l'Ambassadrice la donnoit aux Dames dans un autre appartement, et que dans toutes les sales et antichambres, on distribuoit des eaux à tous ceux qui s'y trouvoient avec beaucoup d'abondance. Dans les mesmes temps furent servies des collations dans six des principales maisons de la place, que Mr l'Ambassadeur avoit arrestées pour y recevoir Mrs les Cardinaux qui ne voulurent prendre ce divertissement incognito, aussy bien que tous les autres princes et grands de cette cour. ... Mr le Duc de Chaulnes ayant fait passer ensuite toute la compagnie dans les appartemens qui regardent la place, laquelle estoit eclairée tant par un grand nombre de flambeaux de cire blanche de distance en distance, et d'une egale hauteur des trois costez, que par deux autres rangs qui estoient aux fenestres du Palais Farnese, jusqu'à la corniche qui paroissoit en feu, il y avoit outre cela 24 fleurs de lis elevées sur des piliers, sur chacune desquelles estoient trois flambeaux de cire blance à l'entour du feu d'artifice, qui estoit dressé au milieu des deux fontaines de la place.(27)

The aim was to depict the Pope as deserving the credit for this peace: thus "pontifical majesty" was shown atop a globe, "saving the world from the fires with which it was threatened."

Below him, Victory offered palm branches, and War surrendered his weapons. The globe seemed to be burning, yet it was not consumed. The Ambassador sent a sketch, pointing out that "ce n'est que le corps du dessein du Chevalier Bernin, sans les ornemens qui l'accompagnerent."(28) (Sketches of the globe and the "ornaments" have survived.) The evening finished with more refreshments, and a fountain of wine for passers-by.

The Duke of Chaulnes returned to France in late August, 1668, having delayed his departure in order to preside at the annual Feast of St. Louis, "avec tout l'appareil possible." This final celebration was especially meaningful, because news had just reached Rome that a son had been born to Louis XIV.

During Chaulnes' twenty-six months in Rome, he had become very close to Jacques II Dalibert: "On n'ignore pas que feu M. le duc de Chaulnes avoit beaucoup d'affection pour M. D'Alibert. ... Je suis témoin qu'il lui écrivoit fort regulièrement," it was later recalled.(29) During the Queen's long absence, Dalibert's principal duty presumably had been to deliver messages to one or another embassy. One can therefore assume that he was the unnamed individual who informed the Ambassador about Christina's doings; that he was the "personne qu'il [Cardinal Azzolino] m'a envoyé exprès" with information about the Queen.(30) Dalibert had a great deal of free time as the Christina-less weeks turned to months and months dragged on into years. He was not getting paid, and the Farnese may well have called upon him whenever they needed decorations, caterers, addresses, recommendations ― in return for the customary purse full of coins or the silver candlesticks that could be hocked. Was Dalibert, for example, asked to find musicians and costumes for the Ambassador's pre-Lenten entertainments? We do not know, but it seems likely. For example, not only could Jacques II Dalibert communicate with the Ambassador, who knew almost no Italian, he was also in a position to engage, on the Ambassador's behalf, the musicians who had performed at the Riario in 1666.

When Chaulnes was again appointed ambassador to the Holy See in 1689, he made Dalibert — who was unemployed, owing to Christina's death a few months earlier ― a part of his staff.(31)

Footnotes

1. BnF, ms. fr. 13053, fols. 47, 48,

June 25 and July 25, 1665.

2. AAE, Rome, 177, fol. 404v.

3. AAE,

Rome, 177, fol. 403ff, Chaulnes to Lionne, Jan. 15, 1667.

4. AAE,

Rome, 181, fols. 91-91v.

5. Clementi, p. 553. In his accounts of the

pre-Lenten festivities of 1667 and 1668, Clementi made a terrible

mistake: he did not realize that Christina was in Hamburg, so he

invented a whole series of activities involving her!

6. AAE, Rome,

181, fol. 110, Jan. 18, 1667, Abbé Machault.

7. AAE, Rome, 181, fol.

130, Jan. 25, 1667.

8. AAE, Rome, 181, fol. 195, Feb. 8, 1667.

9. AAE, Rome, 181, fol. 212.

10. AAE, Rome, 181, 233v.

11.

Information provided in French by Jean Lionnet, Vatican, Barb. Lat.

6368, fol. 574, Feb. 26, 1667.

12. AAE, Rome, 181, fol. 258v, Feb.

22, 1667; and fols. 284-87 for Maffei's description of the float.

13. AAE, Rome, 118, fol. 270, Chaulnes to Lionne, Feb. 22, 1667; and

fol. 277v, written the same day by Abbé Machault.

14. AAE, Rome,

181, fol. 277v, Feb. 22, 1667.

15. AAE, Rome, 185, fol. 183,

Chaulnes to Louis XIV, Aug. 9, 1667.

16. AAE, Rome, 185, fol. 227v.

17. See Ranum, Portraits, pp. 129-130.

18. See Ranum, Portraits,

pp. 529-530.

19. AAE, Rome, 189, fol. 123v, Jan. 24, 1668, Machault

to Lionne, and Chaulnes to Lionne.

20. Virginia Scott,, The

Commedia dell'Arte in Paris, 1644-1697 (Charlottesville, 1990), p.

156.

21. AAE, Rome, 189, fol. 168v, Jan. 31, 1668.

22. AAE,

Rome, 189, fol. 209v, Machault, Feb 2, 1668.

23. AAE, Rome, 189,

fol. 206-206v, Bourlemont, Feb. 7, 1668. The Comica del Cielo

is mentioned in the avvisi di Roma, Vatican, Barb. lat., 6368,

Feb. 18, 1668.

24. AAE, Rome, 189, fol. 218.

25. AAE, Rome, 189,

fol. 240v, Feb. 14, 1668, Chaulnes to Louis XIV; and Bjurström, pp.

78-79, for the drawing.

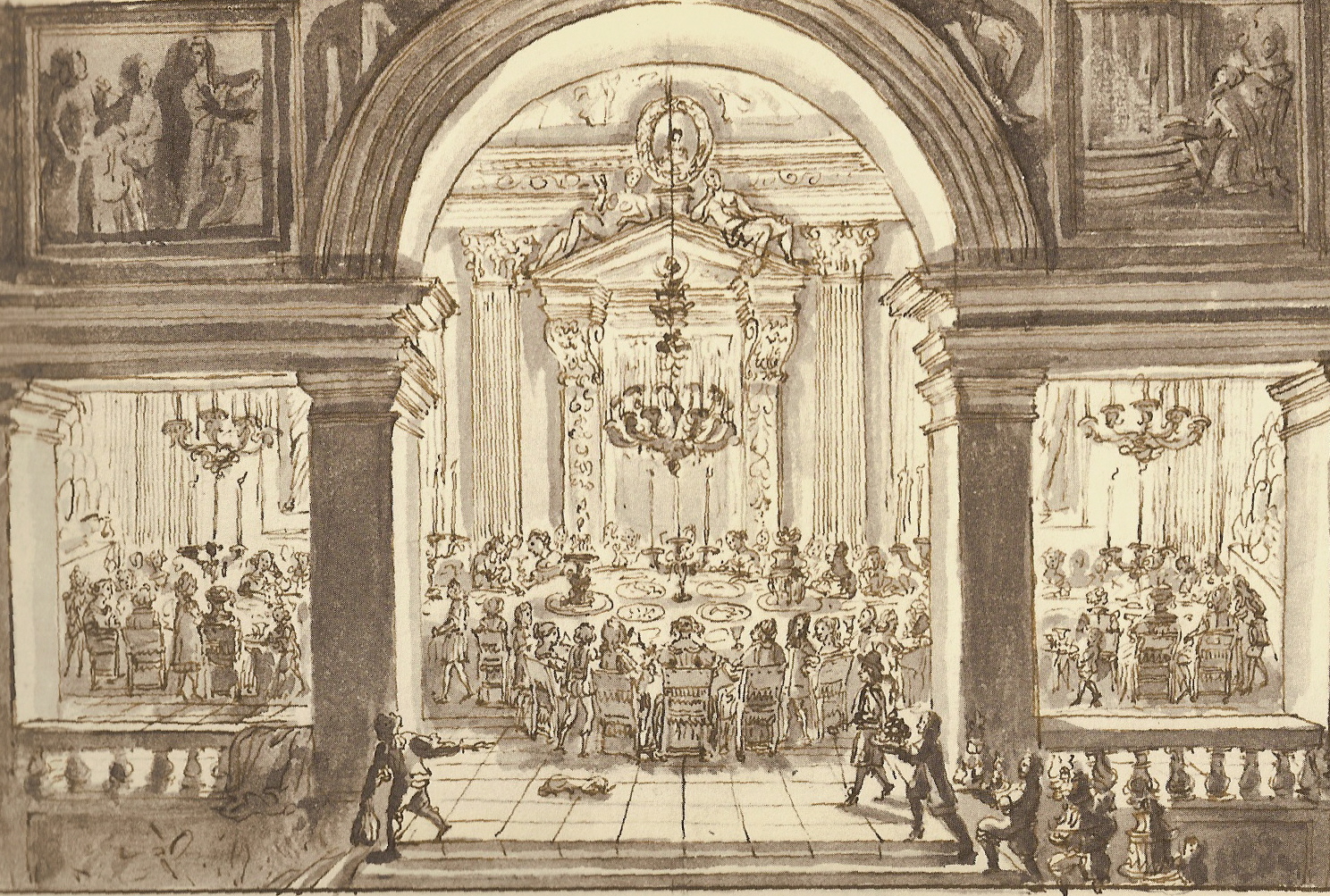

26. AAE. Rome, 192, fol. 13, Bourlemont to

Lionne, July 3, 1668. See Bjurström, p. 61, for a drawing by Sevin that

could well represent this type of event.

27. AAE, Rome, 192, fol.

48-48v. Sevin's drawings of banquets and collations do not represent

those prepared by Chaulnes, but the parties at the Farnese must have

resembled them, Bjurström, pp. 58-67.

28. AAE. Rome, 192, fols.

48v-50, for one sketch; and Bjurström, pp. 48-51 for Sevin's drawings.

29. Fénelon, Correspondance, ed. J. Orcibal (Geneva, 1987),

VII, pp. 155-56; and VIII, pp. 203-04, Oct. 14, 1698.

30. AAE, Rome,

186, fol. 232, Oct, 1667: "l'on a eu nouvelles que la Reine de Suède...";

and 191, fol. 45, May 1668: .

31. Fénelon, Correspondance,

VII, pp. 155-56, Abbé de Chanterac, Oct. 14, 1698.