The

Ranums'

The

Ranums'

Panat Times

Volume 1, redone Dec. 2014

A dot at the beginning of a musical measure:

What did it mean for Marc-Antoine Charpentier?

In my Harmonic Orator, (1) I discussed the dots that sometimes begin a musical measure, and lamented the modern editorial practice that turns that sort of dot into a note that is tied across the bar-line to the final note of the previous measure. I have continued to protest this practice, as in my Musing about the rhetorical implications of such dots in Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre's song.

A reader recently asked questions that rekindled my interest in the subject: Did Charpentier use such dots in his Latin music? And if so, what do they mean?

To answer, I delved into Marc-Antoine Charpentier's Mélanges, turning first to volume I, which contains pieces written in the early 1670s.

Sanctus, sanctus

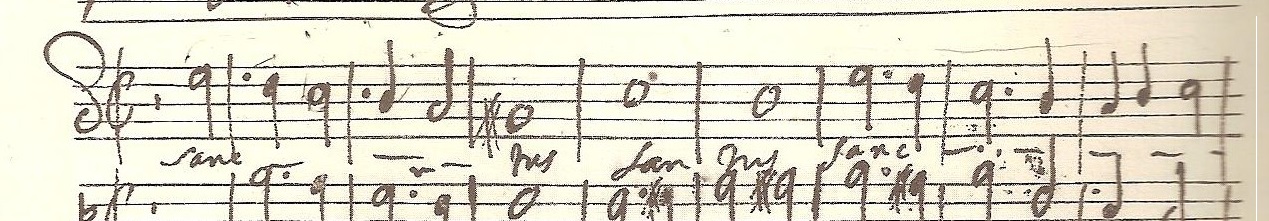

In the Sanctus of his Messe pour les trépassés (fol. 20v of volume I), some of these tantalizing dots appear in the long first syllable of sanctus, which is followed by a second sanctus in which the long first syllable is set to the same dotted rhythm:

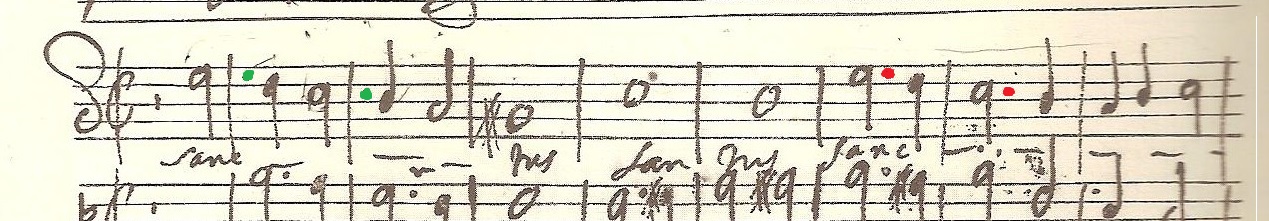

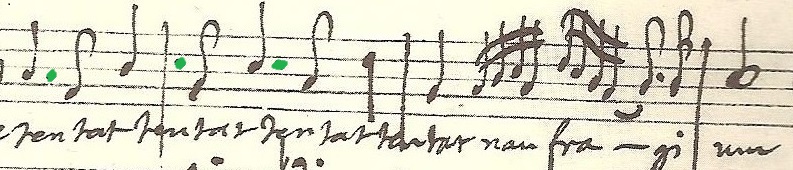

The two notations of sanctus differ only in the placement of the bar-lines! Here are the same measures, but with color-coding.

The first sanctus, with green dots, is metrically out of step with the second sanctus, with red dots. But in each case the first five notes of sanctus are identical: E (dotted half note), D (quarter note), C (dotted half note), B (quarter note) A...

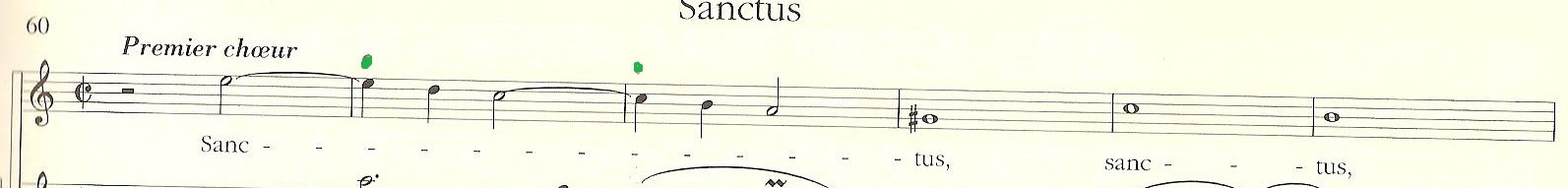

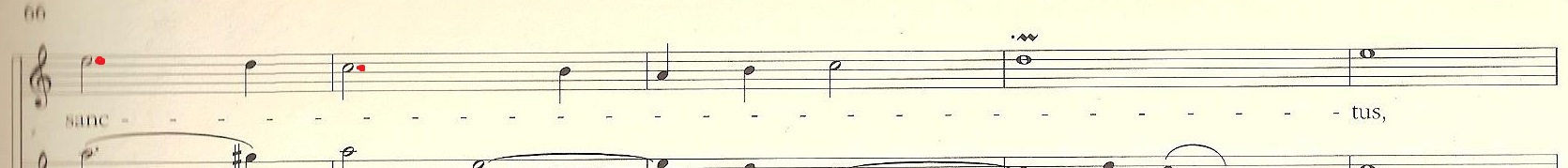

As I pointed out in my introductory words, most modern editors adhere slavishly to an editorial practice that betrays the composer's intentions. Indeed, the following two excerpts from the version of this Sanctus (2) published by the prestigious CMBV raise questions about the wisdom of this editorial practice. (As a reminder, I have added green dots above the editorial tied note in the first appearance of sanctus.) These measures have been transformed into a bland and rather droopy notation that conveys none of the magnificence associated with dotted notation. Indeed, singers are highly likely to declaim the first sanctus differently from the second one. That surely was not Charpentier's intention!

This handful of measures from the Sanctus can teach us other things essential to our understanding not only of Marc-Antoine Charpentier's music but also of his famed rhetorical skills.

First, this brief passage — as Charpentier wrote it — clearly did not expect performers to imagine, when they saw those dotted measures, the sort of editorial changes found in twentieth- and twenty-first century publications.

Second, the troublesome dots in his music have nothing to do with triple-meter rhythms that change into duple-meter rhythms in "hemiolas." (3) Indeed, in Charpentier's compositions these dots at the beginning of a measure appear in duple-meter measures — just as they do in the 1688 Ballard edition of Lully's Thésée. (4)

Third, the fact that Lully and Charpentier both used this notational device — the former in vernacular pieces and the latter in settings of Latin texts — strongly suggests that a dot at the beginning of a measure meant roughly the same thing in Latin and French song, that their meaning applied to pieces in duple meter as well as in triple meter, and that the meaning of these dots was understood by performers at court, in a princely household, in the theater, and in church. (Later in this Musing, we will look more closely one vernacular passage where Lully used these dots.)

Fourth, Charpentier was using these dots early in his career.

Fifth, these dots presumably sent a message to performers — in all likelihood a clue to how best to declaim the text. The examples that follow will suggest a few aspects of this message. Indeed, when this sort of dot is present, the notation are almost certainly is related to the rhetorical skills for which the Journal de Trévoux would later praise Charpentier.

Passages gleaned from volume IV of Charpentier's Mélanges suggest the nature of the message conveyed by this notation. The works in this volume were written for the Guises in 1680-1681, when Charpentier was also composing for the Dauphin. If we find these troublesome dots in this volume, we can presume that they did indeed mean something to performers in general — not solely the musicians at the Hôtel de Guise but also the Pièche ensemble who performed Charpentier's music in the royal chapel.

Tentat, tentat, tentat...

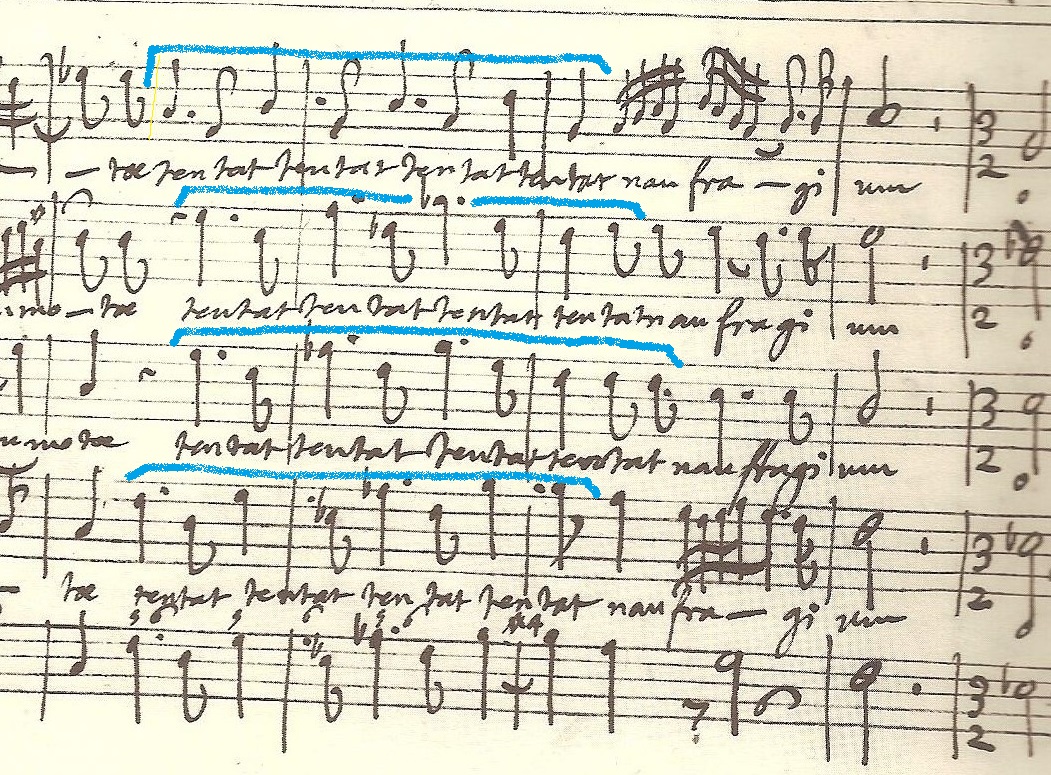

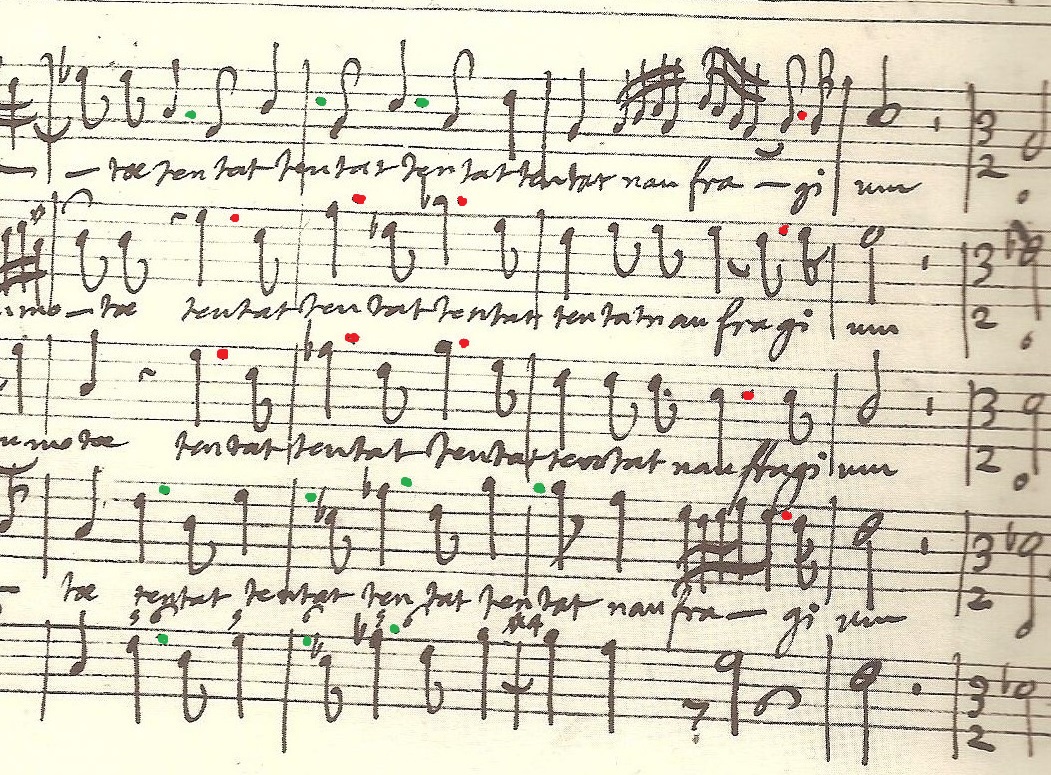

The first example comes from Extremum Dei judicium (H. 401), (5) where long-short rhythms in five musical voices splash against one another in an Imitation (6) of an angry sea. Dots abound here, both at the beginning of measures and also in their more usual places. As the blue brackets show, the word tentat is repeated over and over, to dotted notation.

Tentat is a two-syllable word, a category that Latin grammars of the day describe as forming a long-short unit. (7) This is why the first, "long" syllable of a two-syllable word is often (though not always) given a longer note than the second, "short" syllable. This is why Charpentier set all the ten-'s to a dotted quarter note, and all the -tat's to an eighth note. (8)

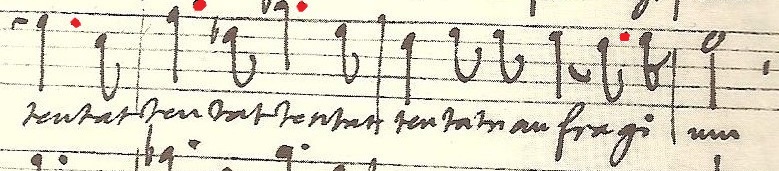

This brings us to the core of the issue: just as in Sanctus, sanctus (above), the rhythmic notation for all these tentat's is the same, regardless of the word's position in the musical measure. The word is notated as long-short, that is, dotted quarter note + eighth note. Here red dots highlight the dotted rhythm as it appears in one of the voices. This particular notation for tentat fits neatly within bar-lines:

The same dotted rhythm is used in other voices, but as the green

dots show, the words are out of step and flow across bar-lines and

beats.

Below, we see all four voices and continuo, viewed together and color-coded. Everyone is singing or playing the same dotted text/rhythm, yet the green dots part ways with the red ones.

Be the dots red or be they green, the notational rhythms look the same. Indeed, looking the same is the key to understanding this mystifying notation. Tentat clearly is supposed to be pronounced with the same long-short speech rhythm throughout. It is the bar-lines that confuse us. Clearly, the singer was supposed to be guided by the "look" of the words and, for these four measures, disregard the presence of bar-lines.

This doubtlessly posed less of a challenge for singers in 1680 than for performers of the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. After all, Ballard's second edition of Bénigne de Bacilly's Airs spirituels (1692) still included a few bar-less pieces. And we can assume that Charpentier's musicians were familiar with Bacilly's bar-less song books: in 1688 their music master was Nicolas Montailly, a student and disciple of Bacilly's.

If an editor were to attempt to eliminate the troublesome green dots in the above passage, and replace them with tied eighth notes, he would obscure Charpentier's message and would give the impression that tentat should be pronounced sometimes with one rhythm and sometimes with another.

Put another way, in both French and in Latin song, dotted notation

was understood to replicate the longs and shorts of a declaimed text.

Even more troubling is the fact that when modern editors eliminate the

troublesome dots (as for Sanctus, sanctus, above), they delete

the rhetorical practices suggested by those dots, in both French

vernacular song and in Latin pieces.

Conclusion: Charpentier's

dotted notation should not be modified in this piece — nor in any Latin

piece he wrote. He expected his singers to imagine a bar-less passage

where some voices adhered to the strong musical beat and others diverged

from that beat.

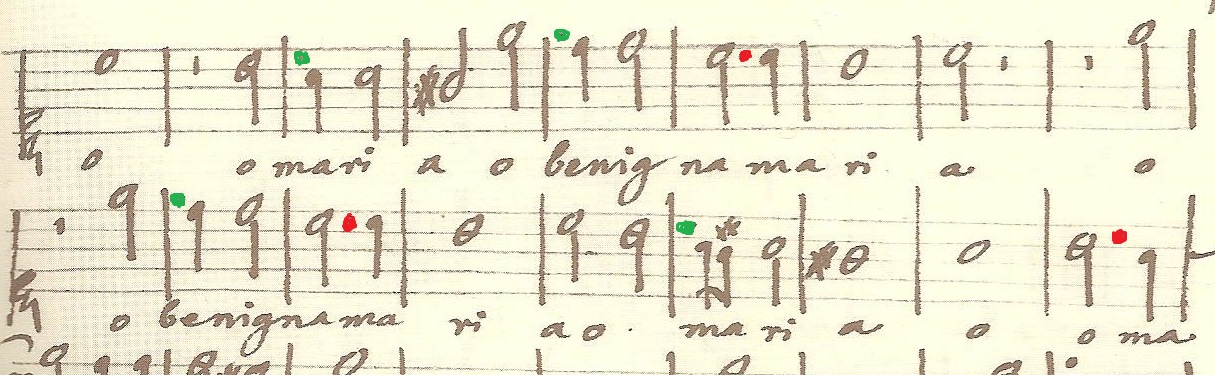

O Maria, O benigna Maria

What are the rhetorical clues implicit in a dot?

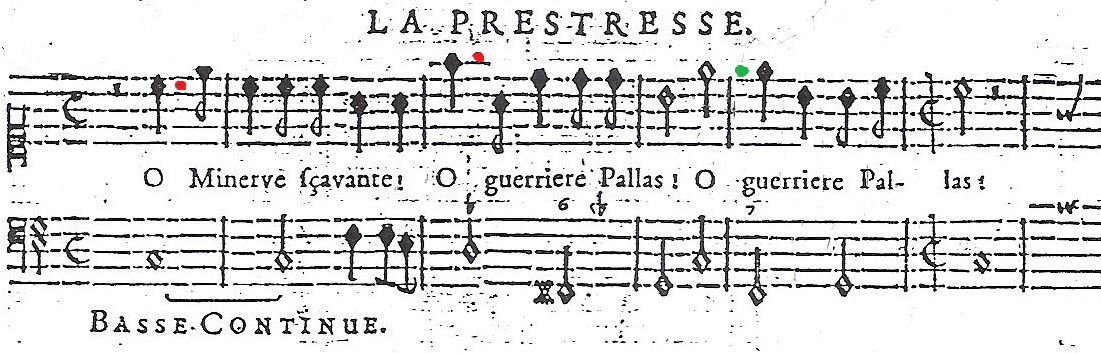

The following excerpt from Lully's Thésée (9) demonstrates one of the principal pronunciation clues provided by a dot, in vernacular music. Three times, the priestess exclaims O! And each time, the O is followed by a dot that reminds the singer to create a brief silence for a comma or an apostrophe. In this context the dot also suggests what can best be described as a "gasp." That is to say, the priestess should inhale suddenly with the mouth open, out of pain or astonishment. After that, she launches the next word by the technique known as doubler or gronder (10) — that is, she "doubles," "grumbles," hums" the consonant: MMinèrve, gguerrière. This is a standard declamation technique that helps singers emphasize key words.

Compare the priestess's Apostrophes to Minerva with the following

Apostrophe to Mary from Charpentier's Inviolata, integra et casta es

(H.26). (11) The example is highlighted with

both red and green dots. Interestingly enough, each colored dot

functions in quite a different way.

The red dots almost certainly convey doubler, gronder.

(12) That is, each red dot precedes an m that can be

lengthened during the time of the dot: O, MMaria, ...benigna MMaria ...

By contrast, the green dots represent the comma that follows the

exclamation O! This implicit comma is omnipresent in vernacular

song, although the dots usually are in step with the musical meter and

behave like red dots. The dot is generally performed as a brief intake

of air ("gasp") followed by a "doubling" of the consonant that begins

the name of the person being adored.

In Lully's Thésée, the

priestess sings: O [gasp] MMinèrve, O [gasp] gguerrière Pallas [silence

for colon], O [gasp at the bar-line] guerrière Pallas ... .

Charpentier's motet is declaimed in a very similar manner: O, [gasp at the bar-line] MMaria, O, [gasp at the bar-line] bbenigna MMaria. (In other words, the O should not be lengthened, and Ma- should not be shortened. Instead, the admiring O is really quite short, and the next measure begins with a brief gasp followed by the "doubled" articulation of MMaria, or bbenigna.) So common is this notational device in vernacular French song that it is inconceivable that a singer would not recognize, here, in Charpentier's Latin text, the familiar rhetorical figure known as Apostrophe.

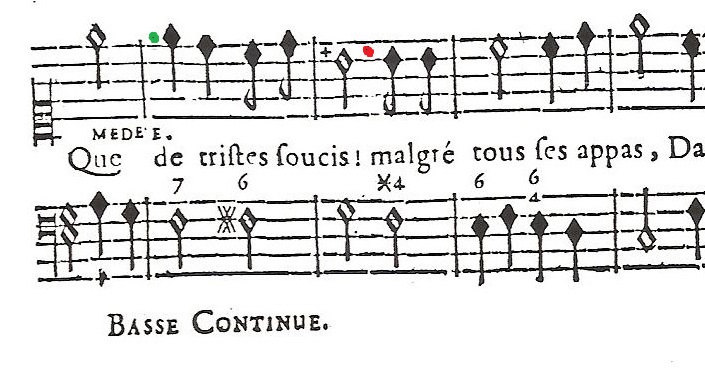

One final, and related example, is Charpentier's use of this type of dot in Médée. (13) Médea sighs as she sings thls line to Jason:

Jason repeatedly echoes her sighing, descending statement, always placing a dot at the beginning of the measure, after Que... The message conveyed by the notation is that both lovers are being dragged off-rhythm by their sighing Que... — which is followed by a gasp that takes up most of the dot and that therefore creates a silence roughly at the bar-line. In other words, they sing a short Que, plus a "gasp," followed by dde tristes soucis! (It would be defective declamation to hold Que for the entire half note, because it would be heard as the long, feminine word queue!) The red dot reminds the singer to make a silence after soucis. (Soucis is the caesura of the 12-syllable Alexandrine line, and caesuras theoretically should be followed by a brief, comma-like pause. In this particular line, the caesura would be rather long, for it would occupy the time appropriate for an exclamation mark.) Then, after "doubling the m of malgré, the singer should continue on to the rhyme (appas): ... mmalgré tous ses appas.

To summarize:

I could go on and on, and perhaps I will one day.

Meanwhile, musicians would be advised to let Charpentier — rather than editing practices that seem to have been invented in the twentieth century (14) — guide their declamation, according to a few simple principles :

Regardless of where the dot falls in the measure, the measure should be performed as written.

When the dot is displaced to the beginning of a measure, it may help to imagine that the bar-lines have momentarily disappeared.

A dotted note often indicates a long-short relationship among syllables.

A dot often suggests a punctuation mark and/or a dramatic, gasping intake of breath.

A dot almost always suggests lingering ("doubling") the consonant that begins the next syllable.

A dot can suggest several of the above rhetorical actions simultaneously.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier was extremely precise in notating Latin

syllable lengths, and the

Jesuits of

Trévoux lauded him for his rhetorical skills. We all can profit from

the acumen of this musical rhetorician, by respecting his choice of

notation rhythms and lengths, and by viewing a dot, wherever it be, as a

clue to pronunciation and rhetoric.

Notes:

1. Patricia M. Ranum, The Harmonic Orator (Pendragon Press, 2001), pp. 296-300. My comments about rhetoric throughout this Musing are based not only upon the contents of this book but also upon insights gained while working with William Christie's Arts Florissants during preparations for Médée and Thésée.

2. M.-A. Charpentier, Messes (Versailles; Editions du Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles, 2002), vol. 4, p. 7. The researchers of the Centre may not even realize the implications of what is clearly an in-house editing style. In the introductory material, the editor generally states something to the effect that "cette édition cherche à rester le plus fidèle possible aux manuscrits de Charpentier"; but although the list of editorial changes includes "some missing ties and slurs" that have been "added using dotted lines," the ties that replace the dots are not indicated by dotted lines. To ferret out these tacit manipulations of Charpentier's notation, performers and scholars are therefore advised to compare printed editions with the Minkoff facsimiles.

3. Ranum, Harmonic Orator, pp. 293-294.

4. Ranum, Harmonic Orator, p. 296, note 13.

5. Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Mélanges (Minkoff), vol. IV, page 168/ fol. 97 v.

6. Ranum, Harmonic Orator, pp. 362-373.

7. For the longs and shorts of French "vulgar" Latin, see Patricia M. Ranum, "'Le chant doit perfectionner la prononciation, & non pas la corrompre,' L'accentuation du chant grégorien d'après les traités de Dom Jacques Le Clerc et dans le chant de Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers," in Plain-chant et liturgie en France au XVIIe siècle, ed. Jean Duron (Klincksieck, 1997), pp. 59-83.

8. We have seen that, in Tentat, tentat, tentat, Charpentier used dotted notes to convey the long-short of two-syllable words. He did the same in vernacular song. If we thumb through Airs sérieux et à boire, ed. C. Cessac, Bulletin Charpentier, no. 20, 2003, we will note that the following words are set to a dotted quarter note + eighth note: her-be (in Brillantes fleurs, naissez); sû-re (in Il faut aimer); u-ne, cet-te (in Ah! Laisser-moi rêver); tris-tes (in Tristes déserts); u-ne (in Quoi! Je ne verrai plus); and so forth. In short, a dotted quarter note + an eighth note conveyed a visual message to singers: this is a two-syllable word composed of a long plus a short.

9. Lully, Thésée (Paris: Ballard, 1688), p. 149.

10. Ranum, Harmonic Orator, pp. 203-215, 249-253.

11. Charpentier, Mélanges, vol. IV,fol. 10 r.

12. Ranum, Harmonic Orator, pp. 203-215, 249-253.

13. Charpentier, Médée, first performed in late 1693 (Paris: Ballard, 1694), p. 12.

14. I do wish someone would track down the inventor of this editorial

practice! I have found no mention of such a notational convention in the

seventeenth- and eighteenth-century musical treatises I consulted for my

Harmonic Orator. Indeed, I wager that the convention was

invented in the early twentieth century, when editions of baroque music

were just beginning to be made.

First published in Volume 1 in 2014 with the URL http://ranumspanat.com/dots_MAC.htm