The

Ranums'

The

Ranums'

Panat Times

Volume 1, redone Dec. 2014

Jacques II Dalibert

secretary to Queen Christina of Sweden and financial and political "operator"

Part 2 : 1666-1689

On May 22, 1666, Christina departed from Rome and set off for Hamburg. She would not return to the Eternal City until November 22, 1668.

(In short, if we suppose that Marc-Antoine Charpentier's "three-year" stay in Rome began at the latest in the fall of 1665 or 1666 and ended during the summer of either 1668 or 1669, it is quite unlikely that he ever composed for Christina. That does not, however, preclude an acquaintance with Dalibert, through friends at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris or through the French Embassy in Rome.)

While Christina was in Hamburg, 1666-68, it was through Dalibert that she kept in touch with the social and artistic events in Rome. A letter dated February 22, 1668, and sent from Hamburg, reveals what the daily conversations described by the anonymous Histoire published by Franckenstein must have been like:

Je vous envoie une lettre pour Danese, rendez-là en main propre, et observez sa contenance pour m'en rendre compte. J'attends de vous la relation des divertissemens de Rome du Carnaval, des chasses, des mascarades, et autre galanteries; soyez ponctuel et ne craignez pas d'être long; car tout ce qui regarde Rome ne peut pas m'ennuyer. Dites-moi aussi sincèrement, si mes appartemens, meubles, et peintures ont plû à l'Ambassadeur [Chaulnes] et à l'Ambassadrice de France. On m'a dit que la de Brun, qui est avec elle, est celle-là même que j'ay vu danser dans les Bals du Roi de France [en 1657]. Je voudrois savoir si cela est vrai, car j'en serois ravie, cette fille étant de ma connoissance ...."(1)

While the Queen was away, what was Dalibert doing, besides sending her gossip?

— He continued his correspondence with Turin, hoping to turn these contacts in to a financial or social advantage for himself and his family.

— He was busy with money-making ventures.

— He continued to carry out his official duties, even if he was not being paid. He therefore visited the French diplomats at the Farnese Palace, to deliver messages from Christina and (the archives suggest) to gossip with his compatriots.

— He consequently was in touch with Dassoucy, whom he may well have met in Florence back in 1659-1661, and whom he almost certainly saw after the poet-musician moved to Rome and made his way into Christina's circle.(2)

(Marc-Antoine Charpentier is known to have been in contact with Dassoucy while in Rome. Can we assume that Dalibert was likewise in touch with Marc-Antoine Charpentier? They had mutual links of friendship and protection to the Luxembourg Palace where to Gaston d'Orléans' widow and daughters resided. In addition, Frenchmen visiting or living in Rome inevitably went to the French Embassy to request passports and letters of recommendation.)

There is frustratingly little in Dalibert's correspondence with Turin or in the letters sent to Paris by the French diplomats at the Farnese Palace ― to shed light on what, if anything, Dalibert was doing at the Farnese while the Ambassador Chaulnes was in residence there, July 1666 to September 1668. All we know is that he and the Ambassador became good friends. (Learn about Dalibert and the Farnese Palace)

On the other hand, throughout this period, or strictly speaking, from 1664 until the late 1670s, Dalibert's letters to the Court of Savoy in Turin reveal a great deal about the man and his character. Some of these letters were addressed to the Duke himself, Charles Emmanuel II. (Born in 1634, the Duke was only a few years older than Jacques II Dalibert.) The letters also train a spotlight on the potentially lucrative ventures that Dalibert was undertaking in Rome. As a result, although sent off to Turin, this correspondence informs us about Queen Christina and her household. Those aspects of Dalibert's correspondence with Turin that focus on music and the arts are presented in a separate section devoted to Dalibert's operatic ventures at Turin.

We know that Dalibert was planning to set up a "mont de fortune" in

Rome. This venture, he thought, would interest the Duke of Savoy,

because a great deal of money could be made.(3) He

also proposed to Savoy an "invention," an "instrument qui sertz à la

nouvelle maniere à semer" ― the inventor of which "est entre mais [sic]

mains aussi bien que son instrument." Thanks to a privilege granted the

Locatellis by the king of Spain, he continued, these inventors have sold

fifteen thousand of these devices in "Espannie," and sales "continuent

toujours le mesme debit.(4)

Dalibert was not

content to simply transmit the latest news: he inquired about musical

events at the Court of Savoy, ostensibly on Christina's behalf: "Je vous

supplie de me faire sçavoir le nom des acteurs et de la troupe de

comediens français que S.A.R. faict venir à Turin." In return, he

implies that he will keep Turin informed about things he learns while

serving Christina.(5)

In August 1668 Dalibert's lottery was still in the planning stage. To keep Turin informed, he promised to give a copy of a text about the lottery to the resident for Savoy in Rome. Since the text ― or perhaps only the letter ― was in Italian, Dalibert commented wittily: "J'aurois mieux repondu en françois, mais j'aurois esté moins intelligible audit sieur Résident." This witticism was followed by an offer of the latest poetry and prose from Paris:

Je vous serois bien redevable, Monsieur, si vous vouliez prendre la peine de sçavoir de son A.R. s'il agrera que je preine la liberté de lui envoyer tout ce qui ce fait de plus gallant en vers et en prose à Paris.(6)

In a letter to the Duke of Savoy he hastened to say that "Je ne demande ni titre ni recompense des services que j'esperois avoir le boneur de lui [S.A.R.] rendre." Barely disguising his hopes of profiting financially from his links to the House of Savoy, he continued:

Apres toutes mes disgraces il me reste encore assez de bien pour obtenir à tous les commandemens dont vostre A.R. me voudroit honorer, sens lui estre à charge et j'ose dire mesme avec quelque esclat. Il est vray que si elle jugeoit que je la puisse servir avec plus d'utilité en me califiant de quelque tiltre come de gentilhomme envoyé ou de resident, la grande depense avec laquelle je pretenderois soutenir ce poste m'obligeroit de recevoir de la liberalité de vostre A.R. le mesme traitement qu'elle feroit à un autre.(7)

In March 1667, Jacques II wrote the Marquis de Saint-Thomas (San-Tommaso), the Duke of Savoy's minister and secretary of state, about his "troubles" after the death of Jacques I Dalibert: "Les embaras dans lesquels la mort de mon pere m'a jette depuis peu de jours ne m'a pas permis de penser à autre chose et j'ai attendu de jour en jour un courrier qui m'obligera à ce que je croy, à partir." By June he was overjoyed to report that his worries had been in vain:

Puisque vous avez la bonté de vous informer de l'estat de mes affaires, je vous diray, Monsieur, qu'elles sont en assez bon estat, et si la fortune m'a auté la melieure partie de mon bien elle m'en a laissé autant qu'il est necessaire pour entretenir ici un train aussi nombreus que le peut tenir dans la bienseance un home qui n'est ni cardinal ni ambassadeur.(8)

The Histoire transformed this salvage of his inheritance into something shameful: "il eut l'adresse de se sauver à Rome, avec plus de cinquante mille livres en argent comptant."(9)

Dalibert also shared with Saint-Thomas certain hopes and frustrations concerning his position as one of Christina's householders. His comments reveal the depth of his ties to the Queen, as well as how tenaciously she kept control over her householders and protegés. Dalibert wanted to replace Commander Gini as the Duke of Savoy's representative in Rome, but he was keeping this ambition secret because, "n'aiant point parlé à la reine ma maitresse de ce dessin elle auroit lieu de le trouver meauvès appres m'avoir honoré de la charge de premier gentilhome de sa chambre et de secretaire de ses commandemens, oultre qu'elle a pour moy plus de bonté que je ne merite." In a bid to make his job application more appealing, he pointed out that he had made many friends and contacts in Rome during his "sejour de neuf ans."(10) (In other words, Dalibert calculated that he had begun to set down roots in Rome in 1658, when he was just embarking on the negotiations that resulted in the marriages of two of Gaston's daughters.)

Alas for Dalibert, the Duke of Savoy concluded that he needed a more experienced minister. Not long after ― doubtlessly owing to Christina's influence the Pope made Dalibert gouverneur des armes de Neptune. The new Governor of Neptune continued pressuring the Duke of Savoy for a position, proposing this time that he be made the ducal agent du clergé.(11) Gifts to the Duke pommades, gloves, and "galanteries" ― were accompanied by pleas that Dalibert be granted a three months' trial in the post he was soliciting. Things looked promising, but after Dalibert insisted upon having full control over the expedition of bulla, the deal fell through in May 1672.(12)

Jacques II remained in Christina's service, but he continued to send gifts to Turin, just as he did to "friends" in Paris: a painting, some portraits. Was he becoming an art dealer of sorts? That seems likely, for he drew up a long list of the paintings at his disposal, including works by Mario Muzzi, Mario de' Fiori, Mattia Preti ("il cavaliere calabrese"), two copies of Caracci, some works by the Tempesta brothers, and a work by Poussin, "qui fait bien."(13)

In the midst of this epistolary exchange came yet another request for a favor from the Duke of Savoy: Would he stand godfather for the Daliberts' son Antonio, born during the summer of 1670, "qui est le seul que Dieu m'a donné." The Duke having agreed, Dalibert thanked him as follows:

Si par un miracle pas moins à propos que surprenant, mon fils agé seulement de quelques cepmaines, en fracassant ses langes ne venoit de prester en mes mains le serman de la fidelité inviolable que nous devons l'un et l'autre à Vostre A.R., la seule chose qui m'afflige dans ce rencontre est qu'il [Antoine] me veut disputer la calité de Vostre tres humble tres obeissant et tres fidelle serviteur.(14)

Dalibert's elation over the arrival of a healthy son after seven years of marriage is palpable. (A second son eventually was born to the couple, joining Antonio and two sisters, one of whom was Christina's godchild.) Above all, this intimate letter reveals a bit of Jacques II's charm and permits us to imagine what his face-to-face conversations with Christina and the Duke of Savoy must have been like.

One of Dalibert's more surprising propositions was an offer of money and mercenaries to the Duke of Savoy: "10,000 pistolles et une centaine de tres bons hommes pour l'argent, bien que je ne sois pas asses puissant pour tenir cette somme dans mes coffres."(15) Somewhat later, Dalibert commented that "l'argent est devenu extremement rare oultre tout cela le plus grand obstaque que j'aie trouvé a esté fondé sur ce qu'etant serviteur de la Reine, la justice ne me pouvoit contrindre en rien." Still, he can loan up to 120,000 [scudi?] and borrow 14,000 more on a rente of his in Rome, his properties in France, and his wife's lands (presumably those in Corsica).(16)

Meanwhile, Commander Gini, the resident in Rome for the Duke of Savoy, had died. Dalibert therefore returned to the offensive, politicking once again for the position. Emphasizing his father's service to Gaston d'Orléans — with whom he shared the position as "surintendant de sa maison" — in December 1670 Dalibert alluded to "la parfaitte cognoisance que 15 ans de sejour m'ont aquis, dans de continuels emplois, jouent [joint] à l'honneur d'avoir servi de pere en fils son A.R. en la personne de feu Monseigneur le duc d'Orleans, son oncle, en calité de surintendant de sa maison."(17) In other words, serving the uncle, Gaston, was tantamount to serving the nephew, Savoy. Hence Dalibert's claim to have served the House of Bourbon, in one or another of its branches and sub-branches, since 1655. (He was not inflating his title in Gaston's household: just out of school, he really had been granted the survivance for that position.)

At the same time Dalibert detailed his current financial situation: he now had 15,000 [scudi? pistoles?] in rentes "que je me suis establi en cette ville sans ce qui me vient de France, jouent [joint] aux appointemens de l'employ," which can "fournir à une depance tres considerable, quand elle est faitte avec esprit et mesure." Though he had been Christina's secretaire d'ambassade and premier gentilhomme for twelve years, and thought he had, in addition, been honored with the position of gouverneur des armes de la province de Neptune, he was willing to drop everything and head for Savoy.(18) "Twelve years" in Christina's household: that is, 1658. Was he exaggerating the length of his service to the Queen? Did he really attract her attention that early, as the Histoire suggests?

To ensure that the Duke of Savoy would not forget him, Dalibert continued sending gifts to Turin. For example, in 1673 he dispatched a portrait, asking his contact to "presenter de ma part à S.A.R. le portrait d'une belle dame, je ne me donne point l'honneur de lui ecrire, crainte de l'importuner."(19) As a result of these gifts, Dalibert dared ask the Duke of Savoy to write the Queen of Portugal, "affin que S.M. me favorise dans une pretancion d'un tiltre."(20)

Upon the Duke's death in 1675, "le Comte Dalibert" turned to the Duke's widow, Marie-Jeanne-Baptiste of Savoy-Nemours, now known as "Madame Royale," the title given to female regents. She was enjoying the power conferred by her position as Regent for her young son, and was using her power of the purse to sponsor musical and theatrical events. Dalibert expressed his hope for continued friendly relations, and he accompanied the letter with "essences, satin de Naples, les gands, et les evantails que ce pais produit." While in Venice in 1678 he sent two paintings to Turin.(21) He clearly was preparing the way for yet another favor. Now that Queen Christina's hold on him was weakening as a result of her inability to pay his wages, Dalibert was prepared to ask permission to withdraw from her household if, that is, he could be appointed agent du clergé for Savoy: "Je m'en aquitteray, d'autant mieus que depuis que la reine a lisancié toutte sa cour, je ne la sers qu'autant que ma recognoisance m'i engage."(22)

He did not hide these plans. In fact, Queen Christina supported the proposal by recommending him to Madame Royale for his loyalty and his willingness to serve:

Al Co. d'Alibert mio segrio dell'Ambasciata che has saputo meritar la mia buona grazia col suo fedele, et diligente servizio di molti anni, porto une dispositne si particolare di giovargli in ogni sua occorrenza che havendomi richiesta di raccomandare a V.A.R. i di lui interessi mi sono indotta à farlo tanto più volentieri quanto che mi persaudo di poter sperare da lei effetti corrispondentei alla mia confidenza. ... Prego pertanto V.A.R. con effacice premura à compiarcersi de favorire il Conte suddetto, assicurandola che a tutte le bontà, ch'elle havrà per lui io sarò per sentirle un'obligo molto particolare.(23)

Shortly after that, Negri, Savoy's representative in Rome, wrote Saint-Thomas about Dalibert. Dalibert was having financial troubles owing to the closure of the Tor di Nona Theater and the outstanding debts it had entailed. These troubles had been compounded by Christina's empty purse. Hence his desire to move to Turin, where he hoped to create an opera house for the Court of Savoy. [For this failed attempt, see the page about Turin.)

Dalibert nonetheless hesitated to leave Christina's service and the protection that went with it:

Egli fu delli riformati [della Corte della Regina] ma supplico la regina di lassarlo continuare nelle sua carica di segretario dell'Ambasciatore senza verun stipendio, solo che di godere la sua protetione, e dalla M.S. fugli concesso, e veramente questo signore la serve con ogni assiduità. Il presente pontificato non è che di danno al signor d'Alibert, mentre S.S. ha prohibito il Theatro delle Comedie, dal qual ricaveva d'effetto 3 mila et più scudi, essendone egli stato l'inventore.(24)

...Questo buon signore viene astretto fortamente da' suoi creditori, i quali non hanno alcun riguardo al danno che ha ricevuto in questio pontificato, e la protezione della regina di Svetia non puol giovargli cosa alcuna: non merita alcun danno perchè è un gentil signore.(25)

He wrote Saint-Thomas, proclaiming his desire to spend the rest of his days in the employ of the House of Savoy:

Je n'ay point de plus forte passion que de sacrifier le reste de mes jours au service de cette incomparable princesse [Madame Royale], que je croy si juste, et si equitable, qu'elle ne voudroit pas permettre que ma reputation souffrist en luy donnant de continuelles marques du desir extreme que j'ay de luy plaire; Vous m'avouerez, Monsieur, que je serois digne d'un reproche perpetuel, si apres avoir possedé des premieres charges de la Cour de France et de Rome, j'allois devenir l'operateur [in the sense of "opera-doer"] de Turin; je ne repugne pas neamoins de donner ce divertissement à M.R. et à la Cour, pourveu qu'il luy plaise de m'honorer du tiltre qu'elle jugera le plus à propos, comme seroit de gentilhomme de la chambre de S.A.R. ou quelque autre qui luy plairoit.

A l'egarde de ce que M.R. a eu la bonté de m'accorder au sujet de sa generosité, je ne demande seulement qu'elle ayt la bonté de me reduire en pension 200 pistoles des 500 qu'elle me donne afin que je ne sois pas blasmé d'avoir quitté tant de choses certaines sans avoir rien d'assuré, les Operas, comme tous les autres divertissemens n'estant appuyez que sur le caprice qui trouve d'ordinaire de grands agremens dans le changement.(26)

Was Dalibert exaggerating here? His contemporaries back in Paris scarcely would have described the position of surintendant to the disgraced Duke of Orléans as one of the "premières charges de la Cour de France."

Just over a month later, Dalibert informed Turin that Christina was refusing to let him leave Rome: "[Elle] m'a expressement commandé de continuer à la servir, me refusant la grace que j'espere obtenir d'elle ...." Since Christina had initially approved his departure, Dalibert argued, perhaps she could be won over if Turin sent him an "engagement positif qui me serviroit d'excuse legitime pour ne pas rentrer [chez Christine], ce qu'elle n'eust pu trouver à redire, m'ayant donné permission de le faire." Indeed, he asserted that it was essential that the House of Savoy give him an honorary title of some sort, "un simple titre d'honneur ... dans tous [sic] les cours du monde les gens les plus ordinaires les obtiennent avec facilité."(27)

Had Christina really gone back on her word? Realizing that Turin was about to make off with her impresario, was she having regrets? Or was he exaggerating, in order to wheedle a firm commitment and an honorific title from the Court of Savoy? He may have been telling the truth, because Christina found a way to restore to him some of the privileges he had lost: his wages (200 pistolles), the coach he had been granted years earlier, and his "government of Neptune,"(28) and she also arranged for permission to create a "gambling academy" an entertainment Dalibert himself described as a "conversation, ou académie de jeu pour les gens de qualité."(29) Was it to these "conversations" that the author of the Histoire was referring when he wrote:

Il donna même pendant quelques jours à jouer dans sa maison, sous la protection de la Reine, autrement il ne l'auroit pû faire, parce que cela est defendu à Rome. Et pour entretenir agreablement les joueurs, il leur faisoit entendre de fois à autre, des concerts de musique, & des instrumens dont la simphonie charmoit l'oreille pendant qu'on vidoit la bourse.(30)

In the end, the Turin venture was a dismal failure! The anonymous Histoire summarized Dalibert's flirtation with the Court of Savoy as follows:

Durant la guerre de Pomeranie [1675-79], la Reine ne recevant plus ses rentes, fut obligée de reformer sa maison, & de congédier la plûpart de ses Domestiques. Le Comte d'Alibert ayant perdu ses apointemens, aussi bien que plusieurs autres, voulut tenter fortune dans une autre Cour, & s'avisa d'aller à Turin offrir ses services à madame Royale qui gouvernoit l'Etat, durant la minorité du Duc à present regnant. Il y fut assez consideré dans les commencemens, mais quand il fut connu à fonds, on n'en fit pas un grand compte, & lui qui croyoit avoir affaire à des Allobroges, trouva dans cette petite Cour des gens si spirituels & de si bon sens, qu'elle ne le cedoit à la Cour de France, que pour le nombre. Enfin le Comte d'Alibert étant envoyé de la Cour de Savoye, où la Cour de Savoye étant ennuyée de lui, il revint à Rome [vers la fin de 1678] où il trouva la Comtesse sa femme qui l'attendoit avec fort peu d'impatience.

Despite the imbroglios at Turin, the aborted project led to the creation of a paying public theater there, with operas during Mardi Gras, in the manner of the Tor di Nona of Rome. Known as the "Teatro Regio," the theater Dalibert had dreamed about became a fact in January 1678 and remained in use until 1814.

May 1678 found Dalibert making yet another offer to lend money to the House of Savoy:

Dans la crainte où je suis que la recolte des bleds en Piedmont ne soit pas aussi bonnes que l'on pourroit souhaiter, j'ay pris les mesures pour en pouvoir avoir dans le commencement du mois d'aoust prochain, 40 sacs en cas que M.R. en eust besoin.(31)

More letters of the sort doubtlessly have been preserved in the Archivio di Stato of Turin, but time forced us to stop with the letters written during the fall of 1679.

The Tor di Nona Theater having been closed, and the theatrical venture in Turin having failed, in 1679 Dalibert turned to puppets. He gave marionette shows in "un Teatro ricchissimo di figure, di scene et buonissmi recitanti et havendo recitato due anni in casa del sig. conte Albert [read: Alibert] secretario dell'Ambasciatore delle Maestà della regina di Svezia."(32) These entertainments found their way into the Histoire: "Il trouva aussi l'invention de faire jouer les Marionnettes chez lui, & d'en faire un trafic."(33)

Christina's death

Queen Christina's health began to fail late in 1688. On March 17, 1689, when a brief amelioration was buoying everyone up, Jacques II Dalibert organized a Te Deum. A contemporary account tells how:

the Count d'Alibert, ambassadorial secretary to Her Majesty, eager to demonstrate his veneration of the Queen and rejoicing over her improved health, decided to sponsor a sumptuous jubilee in the majestic Church of Il Gesu, and in like manner to have a solemn Te Deum mass sung on March 17. He begged the Pope to grant plenary indulgences to all those who confessed and took communion in the church on that day, and who prayed for the recovery of Her Majesty and her preservation.(34)

This event made its way into the Histoire:

Le Conte d'Alibert fit aussi une fête au Jesus [the Jesuit church, Il Gesu], fort magnifique; où l'on chanta une Messe votive de la Vierge, en actions de grace, de la Convalescence de la Reine. Il y avoit fait venir les meilleurs Musiciens de Rome, & l'Eglise étoit parée des plus belles tentures de haute lice de sa Majesté.(35)

In addition, Dalibert paid the debts of 200 people who had been imprisoned for debt.(36)

He was not Christina's only protegé to rejoice publicly: "Il celebre Sr Archangelo Corelli, virtuoso di S.M. fare une sinfonia di bono concerto, con trombe," that was "sonato di più perfetti professori di arco de que[ll]a città ascendo à grand numero.(37)

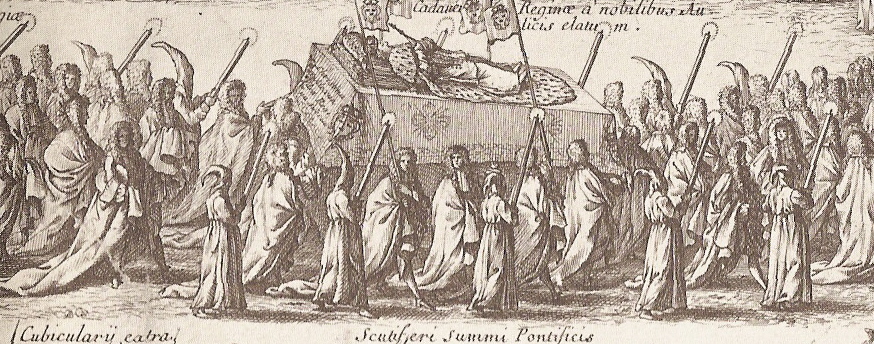

The Queen did not remain well for long. She died on April 19, 1689. Jacques II Dalibert was almost certainly among the cavalieri who marched with her coffin a few days later, as it was borne first to the Chiesa Nuovo, and then to St. Peter's basilica for burial.(38)

Footnotes

1. Quoted by Arckenholz, III, p. 303.

2. Ranum, Portraits, pp.

126-131.

3. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 80, to

Saint-Thomas in 1664, letter number and date missing from my notes;

mazzo 84, no. 147, Dec. 26, 1667; mazzo 86, nos. 175, no. 179, August

1668.

4. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 82, no. 1125.

5. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 82, no. 1129, Nov. 2,

1667.

6. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 86, no. 179.

7. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 84, no. 145, July 1, 1667;

and no. 147, where he openly asks to be named resident for Savoy.

8.

Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 82, fol. 1127 (March 15,

1667) and fol. 1128 (June 8, 1667).

9. Franckenstein, p. 153.

10. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 82, fol. 1128, June 8,

1667.

11. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministre, mazzo 86, no. 173

(1668), and no. 180 (Aug. 13, 1669);

12. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere

ministre, mazzo 91, nos. 294, 297 (Feb. 1672), 302, 308.

13. For

these works, which were proposed in 1672, see Claretta, p. 521; and see

Turin, AdiS, Lettere ministri, mazzo 91, nos. 299, 310; nos. 317-18 for

other lists. Was the painter Nicolas Poussin, or was it Gasparo Poussin,

who back in 1668 had painted the scenery for the Comica del Cielo?

Dalibert presumably knew Maurice Fouchet, on the staff of the French

Embassy in Rome, who proposed to send the Duke "des tableaux osceni, si

je trouve que je puisse immaginer que soyent du gout de V.A.R. Je ne

suis nullement scrupuleux sur cette matiere, ni sur tout ce qui peut y

avoir quelque rapport," Claretta, pp. 531-32.

14. Aug. 12, 1670,

quoted by Cametti, "D'Alibert," p. 348, and p. 349 for Antonio's career.

He died in 1731.

15. Turin, AdiS, Lettere ministri, mazzo 91. no.

313, July 1672; nos. 315-16 list the names of the potential mercenaries.

On Aug. 22, 1672, he announced that he could not send these soldiers:

they had been taken prisoner, mazzo 91, no. 321.

16. Turin, AdiS,

Lettere ministri, mazzo 91, no. 320, 1672.

17. Turin, AdiS, Lettere

ministri, mazzo 91, no. 286, Dec. 13, 1670; and Arsenal, ms. 4214, fol.

85, "les sieurs Dalibert pere et fils, surintendans des finances."

18. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministre, mazzo 91, no. 286, Dec. 13,

1670.

19. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, no. 8,

Sept. 6, 1673.

20. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 95,

no. 12.

21. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, nos. 13

(Jan. 1, 1676), and 18 (Feb. 5, 1678).

22. Turin, AdiS, Roma,

Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, no. 17, Jan. 16, 1677.

23. Cametti, "D'Alibert,"

p. 355, who cites "Montpellier, VI, 22."

24. Ademollo, p. 153, and

Cametti, "D'Alibert," p. 355.

25. Cametti, "D'Alibert," pp. 355-56,

April 13, 1677.

26. April 1, 1678, quoted by Cametti, "D'Alibert,"

p. 356.

27. Turin, AdiS., Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, no. 31, May

28, 1678.

28. Turin, Adi S, Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, no. 23,

undated, but 1678: he claims he lost the governorship because he had

been too long in Turin.

29. Turin, AdiS, Lettere ministri, mazzo 95,

no. 23.

30. Franckenstein, p. 159.

31. Turin, AdiS, Roma,

Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, no. 28, May 18, 1678.

32. Francesco

Mazzetti, an actor who played Harlequin, to Madame Royale, June 25,

1681, quoted by Cametti, "D'Alibert," p. 355.

33. Franckenstein, p.

159.

34. Giovanni Andrea Lorenzani's Raguaglio succincto,

dated March 30, 1689, Vatican (BAV), Urb. lat. 1689, fol 112v. This is

not a word-for-word translation of Lorenzani's account, it is my summary

of the Italian text. Vatican (BAV), Strag 81 (104), Infermità, morte e

funerale della Real maestà, p. 2, asserts that the service at Il Gesu

was "the work of her cavalieri," thereby suggesting that Dalibert did

not act alone.

35. Franckenstein, pp. 271-72.

36. Vatican (BAV),

Urb. lat. 1689, Raguaglio succincto, fols. 115v, 118;

37.

Vatican (BAV), Urb. lat. 1689, Raguaglio succincto, fol. 120.

38. Vatican (BAV), Strag 81 (1-4), Infermità, morte et funerale

della Real Maestà, pp. 3-4, where her cavalieri march in the

funeral procession, as they do in the engraving by Robert van Audenaerd,

Bjurström, pp. 119-120.