The

Ranums'

The

Ranums'

Panat Times

Volume 1, redone Dec. 2014

Christina, Music and Theater

The scholars who worked on Christina and her circle seem not to have doubted that Jacques II Dalibert played a major role in the organization of the Queen's musical events.

Jacques Dalibert, the queen's impresario

Yet no one cites a document that states as much. Rather, when these historians discuss Dalibert, they refer first to a sentence from Franckenstein's edition of the Histoire, to the effect that shortly after arriving in Rome, Dalibert prepared a Mardi Gras float bearing musicians in hopes of catching Christina's attention:

Durant un Carnaval il fit un char des plus superbes, qui représentoit le mont Parnasse avec Apollon & les neuf Muses qui chantoient en Musique, tout cela joint à un concert d'instrumens, faisoit une belle symphonie. Il passa avec ce train magnifique devant le Palais de la Reine, à laquelle il se fit connoître par ce moyen.(1)

On the basis of this late-seventeenth-century statement, Italian scholars studying Dalibert made a chronological leap, from the float of the late 1650s or early 1660s, to his creation of the Tordinona Theater in 1670, and on to the operas he prepared for at Turin in 1678. As my annotated excerpts from the Histoire suggest, this history of Christina's court is factually quite reliable, although a strict chronology and the resultant cause-and-effect is at times quite shaky.(2) In other words, was the float the cause of Dalibert's hiring? Or was preparing floats an obligation that the Queen imposed on him after he became her secretary? Let us scrutinize the available evidence.

When was this float supposed to have been built? The Histoire suggests that the encounter between Christina and the young Frenchman took place very early, perhaps as early as Mardi Gras 1656 or 1657, when Jacques II was making his post-collège trip to Italy. An encounter in 1656 cannot be ruled out, because Christina was in Rome for the entire pre-Lenten period. However, if the brouhaha over his bragging about going to Rome to see Cardinal de Retz delayed Jacques II's departure for Italy, then the encounter with the Queen necessarily took place during or after 1657. Mardi Gras of 1657 must be ruled out: Christina was at Pesaro from October 1656 until spring of 1657, and in any event the Mardi Gras festivities in Rome were canceled that year, owing to the plague. Although Christina set out for Paris on March 12, 1658, the festivities ended on March 5. She could therefore have seen Dalibert's Mardi-Gras float that year. However, we do not know Jacques II's whereabouts in February-March of 1658. Still, that was the year he would later treasure as marking the beginning of his employ by Christina.(3) Mardi Gras of 1659 is another possibility: the Queen was in Rome for Mardi Gras, but I have been unable to determine Jacques II's whereabouts that winter. He had been shuttling back and forth between Turin, Venice, and Paris since late 1658. Did he go to Rome in February 1659 and get caught up in a float-building project, even though he probably had few acquaintances in the Eternal City? Christina was in Rome in 1660, but Dalibert was in France. In 1661 the Queen was in the North, on business, and she remained there until after Mardi Gras of 1662. In short, if the tale of the float is based on fact, the event took place in 1658 or 1659.

The related assertion that Dalibert was her impresario likewise merits a closer look.

To my knowledge, Alberto Cametti, who did intensive research on Dalibert, Christina, and the Tor di Nona Theater, never found a document stating that Jacques II Dalibert was the Queen's "direttore dei spettacoli."(4) He simply asserted it. Thus we too can only presume that organizing spectacles was one of Dalibert's tasks at the Riario. The presumption does make a lot of sense. Who else in Christina's household had such energy, and such a fascination with the spoken and the sung arts? How else could Dalibert have won Christina's support for his opera house, the Tor di Nona? The most plausible answer is that he learned the tricks of the trade at the Riario Palace, 1662-1670. This might explain another passage in the Histoire:

Quand il vouloit habiller ses gens de livrée, il avoit mille inventions pour cela avec les Juifs, sans jamais debourcer de l'argent comptant; tantôt il troquoit une chose, & tantôt l'autre, enfin le Chevalier de l'industrie n'en sçavoit pas plus que lui, & qui voudroit donner le detail de sa vie, feroit un gros volume.(5)

Did Dalibert habitually scour the second-hand shops of Rome for costumes and theater props?

Let us continue to assume, like Cametti, that Jacques II Dalibert was simultaneously Queen Christina's secretary, her impresario, her "first gentleman," and her jester.

My intention here is not to write a complete summary of musical events at the Riario Palace. I will suggest the nature of the "spectacles" that Dalibert presumably directed for Christina. I also present a few facts about the musicians in her employ over the years, and the events in which they performed. These facts come principally from the documents I consulted in one or another European archive, but they are rounded out with other information about music at the court of Christina, 1662-1688, drawn chiefly from Cametti's book and his articles. To do more would be to parrot Cametti, to whom I refer readers.

* * *

Whether Jacques II Dalibert owed his position to a lovely float, or whether he owed it to a letter of recommendation from Lyonne, the French minister for foreign affairs, we know that he was a member of Christina's secretarial staff by June 27, 1662. The date at which his duties expanded to include organizing theatricals can only be guessed — assuming those duties did in fact exist. Deducing the nature of Dalibert's secretarial duties requires little imagination. Deducing how and when he began to deploy his talents as an impresario is considerably more difficult; but here, in more or less chronological order, is what I have found about music and entertainments at Christina's court. To these should be added the tale of his activities as impresario in Turin during the late 1670s. (Learn about his operas in Turin.)

Theatricals, especially during Mardi Gras

In the days leading up to Mardi Gras of 1665, Christina informed a correspondent that "je suis pleine de vigueur, et de santé, fort resolue de me bien divertir ce Carneval." The exact nature of the entertainment she had in mind is not clear. That particular pre-Lenten season, Marie Mancini, the wife of Lorenzo Colonna, arranged several lavish spectacles, including a magnificent float upon which she herself rode. Dumpy Christina could scarcely compete with lovely Marie, so perhaps she didn't attempt it.

Or perhaps the Riario Palace, into which she had only recently moved, did not lend itself to theatricals? That may well be the answer: in June 1665 Christina was planning to build "al suo palazzo un bel theatro, da farvi recitar comedie delle quale [the Jesuit General Oliva] ne prende gran contento." A month later, for two days there were "nel suo palazzo, diversi trattenimenti sensuali, di gioco, musica et altro."(6) By 1666 a theater of sorts was ready. Situated on the upper floor of the palace, it was later described as "la stanza dove si faceva l'accademia la coro d. Musici e Sonatori."(7)

Mardi Gras of 1666 saw Christina sponsoring theatrical performances at her palace. One work was an opera to a text by Crescenzi, with a prologue by her friend Cardinal Azzolino. One of the avvisi di Roma says that, in addition to the "ordinary comedy," an "opera Regia" entitled Amore e Fede was performed, "con richissimi e voghi habiti e belle mutatione di scene."(8) We also know that the musicians described as "musici virtuosissimi" ― were the same Venetians(9) who had performed for the Colonnas in 1665.(10) (A month later, Lionne informed Bourlemont that he had done something ― the details are not specified ― to facilitate Christina's comédie en musique.(11)) Another event sponsored by the Queen was a play by Ferdinando Raggi that was described as sporchissime.(12)

The theatricals were so popular that, on one occasion, the Queen's Swiss guards had to quell a riot after fifty prelates forced as many gentlemen to relinquish their seats.(13) Not long after that riot, Charles Coypeau d'Dassoucy, the French burlesque poet and musician who recently arrived in Rome from Florence, wrote a poem for Christina, asking to be "admitted to her comédie en musique," providing that he would not be beaten up by her Swiss guards:

A la Reyne de Suede pour entrer en sa Comedie à Musique

Quand ce beau Dieu que tout éclaire/ Charmé par les talens divers/ Qu'en vous, grande Reyne on revere,/ Viendroit icy tous les Hyvers/ Tout revetu de la lumiere,/ pour admirer vos beaux concerts,/ Bien que vostre esprit qu'on admire/ Qui tout enchante et tout attire./ Ayme les Vers et les Chansons/ et les doux charmes de la Lyre,/ Vos Suisses ennemis des sons/ Qui frappent les gens sans rien dire ..../ Car ce peuple portant bastons .../ C'est vous, ô Reyne sans seconde,/ Reyne l'honneur de l'Univers,/ Reyne à qui j'ay donné des Vers,/ C'est vous, ô merveille du Monde,/ Où mon esperance se fonde.(14)

These lines contain several important clues about theatricals and music at the Riario Palace. First of all, Dassoucy had already found his way into Christina's circle, for he suggests that it was he who had written "verse" for her and had performed "songs" with his "lyre" ―that is, the theorbe on which he accompanied himself. And now, in March 1666, Dassoucy was hoping to be "admitted to her comédie en musique," a statement that amounted to a request to be admitted to her household.(15)

(In other words, around the time when Marc-Antoine Charpentier arrived in Rome and needed Dassoucy's "bread and pity," Dassoucy had an entrée to the Riario Palace. This suggests that Dassoucy was in close contact with Jacques II Dalibert. It is, however, impossible to say whether Charpentier met Dassoucy at the Riario or elsewhere.)

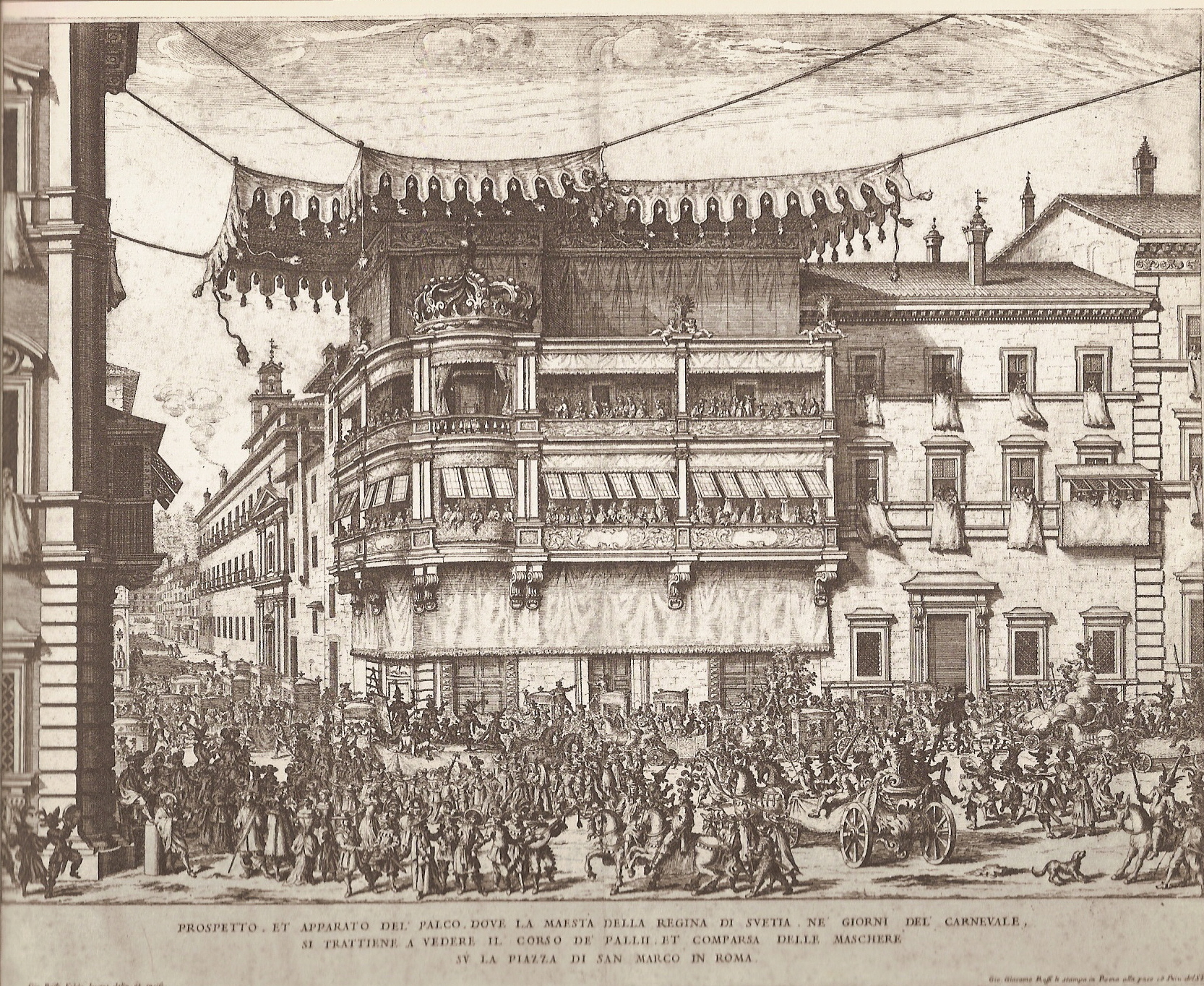

It was also in 1666 that Christina spent 3,000 scudi to have a splendid loggia, decorated with a crown and bearing the motto Qua sta la Regina e patrona di Roma, constructed where the Corso met the piazza San Marco. There the Queen, surrounded by cardinals, not only watched the public spectacles but could be admired herself. Twenty-three cardinals joined her to watch the "masques." She herself became part of the spectacle, for "elle monta à cheval qu'elle travailla en leur presence dans ladite place un long temps."(16) These entertainments were lambasted by the Jesuits, who gave sermons criticizing this "great scandal":

Comme les Cardinaux ont assisté en troupe non seulement à des Comedies lascives et deshonnêtes, mais ont paru en public en un Balcon à la face de tout Rome pour y être Temoins des insolences et des desbauches du Carneval, et tout icy s'entend des Comedies qui se fesayent chez la Reyne de Suede et du Balcon que fit dresser S. Mté au Cours, et [in code:] comme ce cortege public que les cardinaux ont fait depuis quelques mois à la Reyne de Suede a deplu au Palais, l'on ne doute pas que ce Jesuiste a esté suscrit de leur en faire une publique reprehension.(17)

Among the festivities she could see from her loggia was a float prepared by Cardinal Albizi to honor the Queen. The musicians riding it sang a serenata he had written in her honor.(18)

Although Christina made a show of mourning after news of Queen Anne of Austria's death reached Rome circa March 2, she continued the entertainments.(19) The pro-French cardinals proved more respectful:

La reyne de Suede fait reciter les jours gras une comedie en musique avec un grand apparat se devant rejouer plusieurs fois. Elle y convie tour à tour tout le college des cardinaux, et voyant comme Mgrs les Cardinaux de la faction de France s'abstiennent d'aller ainsi que touttes les autres rejouissances publiques depuis la nouvelle de la mort de la Reyne mere, elle fit inviter les cardinaux nationaux ... Tout le college des Cardinaux y a assisté par brigade, chacun ayant voulu donner cette satisfaction à S.M.(20)

Despite a personal invitation delivered by Dalibert, Resident Bourlemont of the Farnese refused to attend.(21)

Citing the following sentences from Retz in a letter dated February 1666, one scholar has proposed that the play performed that year during that Mardi Gras season was Racine's Alexandre:

J'oubliay de vous remercier de la Comedie d'Alexandre qui est fort belle. La Reine de Suede, qui l'a admiré, eut tant d'impatience de la voir qu'elle me l'envoya demander devant que j'eusse le temps de la luy porter.(22)

This hypothesis is very shaky. The Mardi Gras activities of 1666 were already going on when this letter was written. And this is not a discussion of a play currently being played: it alludes to a volume that Retz had just presented to Christina.

Another letter, written the same month, shows just Christina's enthusiasm for French theater. She was hoping to give a performance of Molière's banned Le Tartuffe. In fact, around January 1666 she had ordered Dalibert to ask his correspondents in Paris for a copy of the play. In other words, by 1666 the young Frenchman was at least indirectly involved in organizing an entertainment being planned at the Riario. Hugues de Lionne soon informed Dalibert that Christina's wishes could not be fulfilled:

Monsieur, Ce que vous demandez de la part de la Reyne [de Suède] touchant la Comedie de Tartuffe que Molière avoit comencée et n'a jamais achevée, est absolument impossible, et non seulement hors de mon pouvoir mais de celuy du Roy mesme, à moins qu'il usast de grande violence. Car Molière ne voudroit pas hasarder de laisser rendre la piece publique pour ne se pas priver de l'avantage qui se peut permettre et qui n'iroit pas à moins de vingt milles escus pour toute sa trouppe, si jamais il obtenoit la permission de le representer. D'un autre costé le Roy ne peut pas employer son authorité à faire voir cette piece apres en avoir luy mesme ordonné la suppression avec grand esclat. Je m'estime cependant bien malheureux de n'avoir pu procurer cette petite satisfaction à la Reyne.(23)

This request had, of course, little to do with the Mardi Gras season of 1666, which was already in full swing. In sum, in 1666 — perhaps owing to Dalibert's enthusiasm — the Queen was planning to give French plays at the Riario.

A few months later, on May 22, 1666, Christina set off for Hamburg. She did not return until November 22, 1668.

What might Jacques II Dalibert have done in her absence, beyond his routine secretarial duties? Did he help someone else plan and execute musical events or other entertainments? I have found no document that permits a firm answer. We do know, however, that from July 1666 to mid-September 1668, the Duke of Chaulnes, French ambassador to Rome, was arranging for a succession of devotional and profane events. We also know that during those two years, Chaulnes and Jacques II Dalibert became very good friends. In short, it is highly likely that Dalibert was involved in the comédies en musique, the "operas" sponsored by the Ambassador. (Learn about fetes at the Farnese Palace.)

While the Queen was absent, Dalibert was also busy creating the Tor di Nona theater, a Venetian-style subscription opera house.Although his name is not cited in a document dated July 26, 1666, it would seem that Dalibert and Christina had put their heads together earlier that year, and that she backed this pioneering project morally, if not financially. Dalibert immediately set about turning an existing building into a theater that would be financed in the Venetian way, that is, by permitting private individuals to rent boxes.(24) The auditorium consisted of six tiers, each with twenty-one boxes. Five central boxes were allocated to Christina, the center one topped with a crown.

The Queen marked her return to Rome in November 1668 by having a loggia set up on the facade of one of the houses in the Piazza Venezia for the Mardi Gras season of 1669 thereby calling attention to herself and to the fortunate few who were invited to join her and watch the public festivities.(25) The theatricals she offered to her Roman friends that year were quite baudy. Having learned that Tiberio Fiorilli, a Neapolitan famous for his characterization of Scaramuccia, had been granted a year's leave from the court of France and was in Rome, she hired the comedian and his troop. Two comedies a week were performed at the Riario, Italian on Fridays and Spanish on Sundays. Eleven cardinals attended the first performance. Christina and her joyful response to the troop's off-color humor were part of the spectacle: "la maggior parte delle persone ci vanno per osservare Sua Maestà nelli applausi che dà alli Comici, quando dicono qualche belle botta etiandio grassissima, ride, gode si volta, ridendo, alli cardinale." Christina found a way for Ciccolino, her "ottima musici," to sing during the play.(26)

Mardi Gras of 1669 was a year of bals à la française. There was a festo di ballo at the residence of the Duke of Sforza, "con balli alla francese et gran colatione di dolce." The Marchese Paliotti organized a similar ball. So did Hugo Maffei, the Italian attaché at the Farnese. The French were astonished:(27)

Les mascarades sont ici continuelles et les bals à la françoise sont introduits, ce qu'on ne croioit jamais pouvoir reussir. On en fait sept à huit où se sont trouvez toutes les princesses de Rome s'efforçant à dancer à la françoise. Il s'y est trouvé plusieurs cardinaux ... et grand partie de la prelature; on m'y mena hier et j'y vins danser sept ou huit fois.(28)

It is not clear whether Christina ― who back in 1656-1657, in Paris, had been mocked for her dancing ― sponsored balls that year, in addition to her theatricals. Still, the mere fact that the Histoire alluded to this French craze suggests that the Queen was somehow involved:

Les divertissements se succédoient les uns aux autres, on donnoit ordinairement le matin à la dévotion, et aux affaires, après le repas qui étoit d'ordinaire abondant et servi d'une propreté extraordinaire (car on commençoit à se traiter à la Françoise) on alloit à la Comedie, et à l'Opera, où il y avoit des machines surprenantes, ou bien on entendoit une serenade composée d'une excellente musique, mêlée de concerts, et d'une sinphonie charmante. ... Les dames étoient toutes galantes, on introduisit alors les modes Françoises, et elles parurent si charmantes sous ces habits, qu'elles n'on pu se resoudre depuis à quitter ces modes où elles ont toujours rencheri, en sorte qu'à present [1697] le luxe est excessif à Rome.(29)

We can, of course, only conjecture how active Jacques Dalibert may have been in promoting French culture that year.

Christina's loggia, and her theatricals, plus the French-style balls of 1669, were rounded out with an opera, Acciaioli's Empio punito, performed at the Colonna residence. (Owing to the small size of her own theater at the Riario, Christina rented the theater of the Colonna palace for three years, until the Tor di Nona should be ready. She contributed over 6,000 scudi to the overall costs of the opera, which boasted at least ten scene changes.(30) This venture, on which the Queen collaborated with Marie Mancini Colonna, was well received: "Fu tutta bella, le appartenze bellissimi; sala, galleria, anticamera, selva, giardini capricciosissimi."(31) The performers were excellent, their costumes superb. In addition to the Italian opera, a "French comedy" was performed, intermingled with music and a ballet choreographed by Marie Mancini herself: fourteen nymphs and "French people" represented the four winds.(32) The audience was entirely male, although Mme Colonna was permitted to view the spectacle incognita. At one performance twenty-six cardinals, "tutto il sacro Collegio," were present.

Dalibert's Tor di Nona Theater opened for Mardi Gras of 1671. For several years, Christina basked in the glory it conferred, ensconced in her regal box:

On introduisit alors les Comédies publiq [sic]; durant le Carnaval, à Torra di Nona, par les soins du Comte d'Alibert & de ses Associés; on y pratiqua une somptueuse loge pour la Reine d'une magnificence extraordinaire, où les dorures & les autres ornemens n'étoient pas épargnez, tapissé de damas & autres riches étoffes à dentelles & franges d'or. Cette loge pouvoit contenir 15 ou 16 personnes, & il y avoit toujours dix ou douze Cardinaux qui venoient à la Comedie pour faire honneur, & Compagnie à la Reine, aussi bien en la place St Marc, au coin de la rue St Romuald, où elle avoit loué un petit palais, pour voir les mascarades dont tout le cours est rempli durant le Carneval. La Reine quoy qu'elle eût en ce tems-là passé sa quarantiéme année, conservoit encore beaucoup de brillant. Enfin l'ouverture du Theatre se fit, & les comediens reussirent au gré de tout le monde, d'autant plus que sa Majesté y fit introduire de belles chanteuses, qui charmoient les oreilles par la douceur de leurs voix, & les yeux par les agrémens de leurs personnes. Entre les Cardinaux qui frequentoient la loge de la Reine, le Cardinal Benoit Odescalchi n'y manqua jamais un soir, durant les cinq années que la Reine maintint sa loge au theatre.(33)

Each year Christina put her imprint upon the operas performed at the Tor di Nona. For example, one of the two "comédies" performed there during the pre-Lenten season of 1674, included some "accommodements de la Reine qui ont eu un aplaudissement universel."(34) She was also active in planning the actual performances, to the point of corresponding with the Duchess of Mantua about theatrical troops.(35)

Events at the Tor di Nona, and its unfortunate fate, are the subject of a thick book by Cametti. Readers are referred to that volume. Very briefly, this is the story of the unfortunate undertaking: Clement IX had looked favorably upon the theater, but he died before it was completed. Christina asked his successor, Clement X, for permission to hold public performances, but she went about it so tactlessly that the Pope granted the permit to Dalibert's competitor, Acciaioli. By cooperating, the two rivals managed to open the theater in 1671, but Dalibert and Acciaioli soon were arguing about unpaid bills. Christina was no help, for her contributions did not go beyond the subscription for her five boxes. Performances were held during the pre-Lenten weeks of 1671, 1672, 1673, and 1674. The following year was an anno santo, with no public theatrical performances. Then, in September 1676, Innocent XI was elected pope and, although he had been one of Christina's most frequent guests at the Tor di Nona, he banned all forms of public theater. The Tor di Nona closed and did not reopen until 1689.

That did not stop Christina from sponsoring theatricals: she commissioned an opera from Scarlatti for performance at the Teatro del Collegio Clementino; she apparently arranged a performance of Pasquini's Il Lisimaco at the Riario in 1681; and in the final years of her life she and Abbé Guidi worked on a pastoral and an allegorical "serenade" the latter to be set to music by Scarlatti.(36)

Music and musicians

We know that music was a pillar — perhaps the central one — of the Queen's entertainments. It is not clear how many of her chambermaids, ladies in waiting, valets, and gentlemen could play or sing, but we know that some were very talented. We also know that highly reputed musicians and composers contributed to Christina's fetes, as "extraordinary" artists.

For example, by July 1656 Giacomo Carissimi, the chapel master at the Jesuits' German College, was "already" one of her "actual domestics and servants." To ensure that the famous composer would remain loyal during her forthcoming visit to Paris, on the eve of her departure she issued a statement that served as the courtly equivalent of the brand burned into the hide of a steer:

On account of the virtues recognized in Iacomo Carissimi, and because of the perfection he enjoys in his profession of music, and having resolved to take him into Our service as Maestro di Cappella del concerto di camera, and having already had him enrolled among Our actual domestics and servants, with the effect that he ought to enjoy in every place the due advantages, honors and prerogatives which all Our servants and domestics ought to enjoy, and wishing that, in every necessity, it be known to everyone that the aforesaid Iacomo enjoys, with this character and quality, Our royal protection, thus it is that we attest to him with the present [document], to whoever may see it, making known that the same Iacomo is Our actual servant, and Maestro di Cappella del Concerto di Camera. We command all those who are dependent on Us to recognize, admit and esteem him as such, just as we also assure all others of remembering and being pleased at the esteem which, out of regard for Us, they shall be pleased to show him.(37)

(Jacques II Dalibert would allude to benefitting from the same sort of protection.(38)) True, the proclaimed reason for this document was to make the appointment official. But its principal motive was clearly stated: the Queen was making it "known to everyone" that the composer "enjoys Our royal protection." In other ways, even in her absence, Carissimi was her property.(39) And once you were her property, you remained so, until she agreed to give you leave to serve someone else.(40) In other words, from 1656 until Carissimi's death in January 1674, Christina felt entitled to inform him of her desire for some "chamber" music composed by him secular "chamber" music, rather than the religious music or oratorios that could be considered part of the the German College's monopoly over Carissimi. This of course suggests that Jacques II Dalibert had more than a nodding acquaintance with Carissimi. (See my Musing on Carissimi and Charpentier., and some irrefutable proof that the two musicians saw one another frequently.)

(In other words, while Marc-Antoine Charpentier was in Rome, "seeing Carissimi often," Carissimi, like Dalibert, belonged to Queen Christina of Sweden. We do not know where Charpentier met Carissimi. Was it at the German College? Was it at the Riario?(41) )

A decade later, during a long stay in Hamburg, Christina wrote a letter to Dalibert that reveals just how possessive she could be. She was determined to regain exclusive control over "Ciccolino" (Antonio Rivani), a castrato who had entered her service circa 1662 and whom she had been paying 40 scudi a month.(42) Unemployed and unpaid owing to Christina's absence, Ciccolino had gone to Turin in the spring of 1667. (I do not know the date, but Rivani also had links to Florence, which had recommended him to Grimani in Venice.(43)) At first the Queen allowed herself to be soothed by Azzolino's assurances:

J'approuve tout ce que vous avez fait avec Cicolino et suis tout à fait de votre sentiment: mon inquiétude sur son sujet est passée, car le temps m'a découvert que tout ce qu'on disait de lui n'était que des rodomontades allemandes, mais devant de m'être éclaircie, je craignais qu'il ne me quittât pour le gros prince de Lunebourg; mais je suis sortie entièrement de ce doute.(44)

She subsequently had Ciccolino notified that she wanted him to return to Rome. To no avail. She therefore ordered Dalibert to get in touch with the singer:

Je veux qu'on sache qu'il n'est plus au monde que pour moi, et que s'il n'y chante pas pour moi, il ne chantera pas long temps pour qui que ce soit. Quoique il ce soit [sic] s'il est sorti de mon service, je veux qu'il y rentre, et s'il est sorti, tachez de déclarer mes sentimens d'une manière qu'on fasse passer l'envie aux gens de lui faire l'amour, car je veux le conserver à quelque prix que ce soit. Et quand même on voudrait me faire croire qu'il a perdu la voix, tout cela n'y feroit rien, car tel qu'il est, il doit vivre et mourir à mon service, ou malheur lui en arrivera. Tachez de me rendre compte de cette commission d'une manière que j'aye sujet d'être satisfaite de vous.

Ciccolino got the message. In 1669 he was back in Rome, singing for Christina.(45)

If Jacques II Dalibert was, in fact, the Queen's impresario, he certainly was not dispensable. She had other courtiers to whom she could turn. For example, while in Hamburg in 1667, she learned of the election of Pope Clement IX. She immediately ordered a "messe pontificale qu'elle fit chanter en musique dans la plus grande salle de sa maison, qu'elle avoit fait accommoder en Chapelle, ayant jugé sa Chapelle ordinaire trop petite pour la fonction de ce jour-là." The mass was followed by a dinner and fireworks. The "heretics" of the city, attracted by the 600 wax candles and lamps that illuminated her residence, promptly got drunk on the free wine that poured from a fountain.(46)

In October 1672 Christina wrote some letters of recommendation for two of her household musicians, one to Grand Duke Cosimo III of Tuscany, the other to the wife of Ambassador Grimani of Venice doubtlessly a relative of the Grimanis who had created the Teatro dei santi Giovanni e Paolo several decades earlier and who would soon collaborate with Jacques II Dalibert:

Ayant donné permission à Nicolas Coresi, et à sa femme [Antonia], mes musiciens, d'aller à Venise je leur ay accordé aussi l'appuy de cette lettre aupres de Vous, pour vous prier de les favoriser de votre protection, vous assurant que je vous seray redevable de toute l'assistance et de toutes les faveurs qu'ils recevront de vous à mon esgard ...(47)

Antonia was a "famosa cantatrice che, quasi nouvo sirena, addormentava i cuori degli astanti con la soavità degli accenti."(48) From 1665 to 1667, she had been one of the leading singers at Faustini's opera house in Venice.(49) Both Coresi and his wife had sung at Dalibert's Tor di Nona theater in 1670. Now, in 1672, they were off to Venice. The couple had attracted the attention of the music-loving Duke of Mantua, who asked Christina to allow them to stop in Mantua and participate in a court opera. Four months later, the Coresi resurfaced in the Queen's correspondence, when the Duke of Mantua praised "la virtu nel canto di Antoinia Corresi serva de V.M." He added that "Jo disposto di far recitar nel mio teatro un opera musicale," and so he hoped that Christina would allow Antonia to sing.(50)

In 1681 Corelli dedicated his first published work to her. She also recognized the talents of a young man named Scarlatti and offered him her protection.(51) Christina continued to call upon Corelli. For example, in 1687 the Riario Palace was the scene of three musical evenings honoring the arrival of Castlemain, James II of England's ambassador. A cantata was performed by a choir of 100 singers, accompanied by a string orchestra consisting of 150 players directed by Corelli. This was one of the largest orchestras hitherto heard in Rome.(52) The Queen did not restrict her entertainments to plays and operas: in March 1685 she hired a troop of acrobats, who walked tightrope.

Christina had several young female musicians in her household: Maria Landini, a singer, and Angelica and Mariuccia, her daughters by the Marquis del Monte. The girls sang, as did Angela Maddalene Voglia ( "la Giorgina"), who also played the lute, the theorbo, the spinet, and the harpischord.(53)

Some of these women performed at a lavish musical event organized in 1688 to honor French Ambassador Lavardin. A description of the fete was preserved in the Histoire. On a warm summer evening an "opera," a "serenade," was performed in the gardens. Del Monte, one of the Queen's gentlemen,

persuada la Reine de faire une serenade en dépit des chagrins qu'elle recevoit du Pontife, d'autant plus que la belle saison le permettoit. On fit des couplets de chansons, & des recits qu'on devoit chanter, avec des coeurs [choeurs] d'instrumens: les plus fameux musiciens de Rome furent de la partie, avec deux des meilleures chanteuses de la Reine, la Georgina, ou Angelique, & Manouche ou Marote. ... On dressa un amphitheatre dans un petit Jardin de Jasmin, de l'appartement du Marquis Delmonte, qui donnoit sur la rue, vis à vis le Palais de la Reine. On n'a jamais vû tant d'apprets, car on fit quantité d'echaufauts pour les Dames ...; on fit aussi plusieurs repetitions dans le grand Salon de la Reine, dont le dernier fut extraordinaires par cent sortes d'instrumens, & de belles voix, les Illuminations respondoient à la Simphonie, qui étoit charmante. ... La reine contente au dernier point de la reussite de son opera [sic] fit l'eloge du Marquis en sa presence.(54)

The Ambassador's trumpeters made the garden echo to the popular French song Les Flons Flons, which the audience began to sing.(55)

A few months later, Christina fell ill. She died on April 19, 1689.

Footnotes

1. Franckenstein, p. 153.

2. Nor

are modern interpretations of Franckenstein's statement necessarily

consistent: Clementi states quite firmly that the float was built for

Mardi Gras of 1671, p. 583, while Cametti , "D'Alibert," p. 342, more or

less accepts Franckenstein's chronology.

3. Turin, AdiS, Roma,

Lettere ministre, mazzo 91, no. 286, Dec. 13, 1670: he claimed to have

been in the Queen's service for "twelve years."

4. Cametti,

"Cristina," p. 654; Cametti, "D'Alibert," p. 344, who writes: "... la

sua attività si esplicava nell'apprestare spettacoli nel teatro privato

della Regina e nel sopraintendere ai suo virtuosi di musica."

5.

Franckenstein, p.160.

6. BnF, ms. fr. 13053, fols. 47, 48, June 25

and July 25, 1665.

7. Christina Queen of Sweden — a

personality of European civilization, catalog for the exhibit at

the Nationalmuseum of Stockholm, 1966, p. 62.

8. Vatican, Barb.

lat., March 6, 1666.

9. Back in 1988 the regretted Jean Lionnet

shared with me his strong belief that, based on the "Libri di punti" of

the papal chapel, the composer of Amor e Fede was "very

probably" Mario Savioni, and the singers were recruited from the papal

chapel: Isidoro Cerruti (B), Giovanni Ricchi (T), Mario Savioni (A),

Giuseppe Fede (S) and Giuseppe Vecchi (S), the latter two castrati. For

1667, when Ambassador Chaulnes called upon the musicians who had

performed for Christina in 1666, Lionnet noted that Savioni was again

frequently absent, as were Cerruti and Bonaventura Argenti, another

castrato; but Ricchi, Fede and Vecchi missed few chapel services.

Lionnet's hypothesis conflicts with the evidence found in Venice and

cited by Clementi, p. 549. And so it is more or less demolished by the

fact that one of the performers was a woman, a singer known as "Maria

Vittoria," Clementi, p. 553.

10. Bjurström, p. 72; Clementi, p. 549,

who cites the avvisi di Roma for Feb. 13, in the Venetian archives.

11. AAE, Rome, 23, fol. 175. March 20, 1666.

12. Cametti,

"Cristina," p. 653, and Clemente p. 551, citing the avvisi di Roma of

Feb. 26, March 6 and March 13.

13. Clementi, p. 551.

14.

Dassoucy, Les Rimes Redoublés de Monsieur d'Assoucy (Paris,

1671), p. 132.

15. For Dassoucy in Rome, see Ranum, Portraits,

pp. 128-130

16. AAE, Rome, 175, fol. 172.

17. AAE, Rome, 175,

fols. 36, 120v.

18. AAE, 175, fol. 126, Abbé de Santis, March 6,

1666: "composed by himself"; and Clementi, p. 550.

19. AAE, Rome,

175, fol. 8, Retz to Lionne, March 2, 1666: "Dès les premières nouvelles

que nous eûmes icy ... de la mort de la Reine mere je m'abstiens d'aller

aux Comedies que la Reine de Suède fait faire chez elle." He had an

audience with Christina that very day, during which the Queen sat under

a canopy draped in the colors of mourning, fol. 32.

20. AAE, Rome,

175, fol. 36, Bourlemont to Lionne, March 2, 1666.

21. AAE, Rome,

175, fol. 36v, March 2, 1666.

22. AAE, Rome, 23, fol. 174, Retz to

Lionne, Feb. 16, 1666; R. Chantelauze, Le cardinal de Retz et ses

missions diplomatiques à Rome (Paris, 1879), pp. 425-27.

23.

AAE, Rome, 174, Feb. 26, 1666, Lionne to Dalibert.

24. See the

Glixons, especially chapter 2.

25. Georgina Masson, Queen

Christina (London, 1968), p. 348; and AAE, Rome, 196, fol. 30v,

which names participants and refers to horsemen decorated with flowers.

26. Masson, p. 349; the source is the Archbishop of Genoa, quoted by

Clementi, p. 573; and also Cametti, "Cristina," p. 653.

27. AAE,

Rome, 196, fols. 30, 433.

28. AAE, Rome, 196, fol. 419v, Abbé

Servien, Feb. 26, 1669; these balls are echoed in Franckenstein, pp.

57-58.

29. Franckenstein, quoted by Clementi, I, p. 568.

30.

Cametti, "Cristina," p. 654; Bjurström, p. 97.

31. Ademollo, p. 112.

32. Clementi, pp. 578, 581.

33. Franckenstein, pp. 60-61.

34. Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo 95, no. 10, Dec. 21,

1673.

35. Montpellier, I, fol. 250, April 1, 1670. The troop

included "L'Hortensia," "Lucinda" and "Traffaldino."

36. Cametti,

Tordinona; and Bjurström, pp. 100ff.

37. Translated by

Thomas D. Cully, Jesuits and Music: I (Rome, St, Louis, 1970), pp.

178-179, and p. 337 for the original Italian.

38. Turin, AdiS,

Lettere ministri, mazzo 91, no. 320, 1672: "... étant serviteur de la

Reine, la justice ne me pouvoit contrindre en rien."

39. See Ranum,

Portraits, pp. 116-117.

40. Christina, wrote Dalibert on

May 28, 1678, "m'a expressement commandé de continuer à la servir, me

refusant la grace que j'espere obtenir d'elle," that is, to leave her

household and work in Turin, Turin, AdiS, Roma, Lettere ministri, mazzo

95, no. 31.

41. See Ranum, Portraits, pp. 117-18.

42.

For "licences" to sing for others, see Glixon, pp. 178-80.

43.

Glixon, p. 182, n. 34. Their index merges Antonio Rivani and Paolo

Rivani.

44. Bildt, p. 328, from Hamburg, Mar. 23, 1667.

45.

Quoted by Cametti, "Cristina," p. 648; and p. 649 for the efforts to

make him return.

46. Montpellier, XI, fol. 267.

47. Montpellier,

VI, fol 33, Oct. 1, 1672, and a similar letter to "Madame Grimani"; see

also a letter about them from Cosimo, dated that same month, I, fol.

180, and another from Christina to Cosimo, recommending Coresi's

relative, 1671, VI, fol. 57.

48. Cametti, "Cristina," p. 649.

49. Glixon, p. 203.

50. Montpellier, I, fols. 180, 236; Cametti,

"Cristina," p. 650; and Glixon, pp. 178-80, on permissions to sing for

others.

51. Cametti, "Cristina," pp. 646-47; Masson, p. 382.

52.

Masson, 382; Cametti, "Cristina," pp. 645-46; and for a description of

the "academy," Vatican, 10227, fols. 129-30v, 136-40.

53. For their

careers, see Cametti, "Cristina," pp. 650-53.

54. Franckenstein, pp.

203-05.

55. Masson, p. 383, which merges three distinct allusions to

Lavardin: Franckenstein, pp. 203, 237, 266-67.